Carolee Schneemann - Carolee Schneemann - Exhibitionmfc-michèle didier | Paris - Brussels - PARIS

Exhibition from September 13 to November 9, 2019

Opening on September 12, from 6pm to 9pm

At 7.30pm during the opening: conference by Emilie Bouvard

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) was a painter... as well! Throughout her career, she constantly reminded us that performances, films, photographs, texts were extensions of her paintings. The striking omnipresence of the female nude throughout her work was the better to elude the taboos of the time: “As a painter, I had never accepted the visual and tactile taboos surrounding specific parts of the body”1. By using her body as material, Carolee Schneemann reclaimed the female nude: far from the objectification of the nude present in classical art, Schneemann’s body was a subject, defiant, irrepressible and confrontational. She was a feminist trailblazer who used her body as a tool for advocacy, thereby distancing herself from the traditional representation of a model. The question Carolee Schneemann asks is whether the female body can be both an image and an image-maker, in a world where role models were scarce: "I decided a painter named 'Cezanne' would be my mascot: I would assume Cezanne was unquestionably a woman — after all the 'anne' in it was feminine. Were the bathers I studied in reproduction so awkward because painted by a woman? But 'she' was famous and respected. If Cezanne could do it, I could do it."2

As well as pushing the body beyond its limits, the images produced by Scheemann in her films, photographs or performances were later transformed through painting. Breaking with centuries of art history, her painting modifies the image rather than creating it. As such, she is positioning herself in the continuation of the abstract expressionist movement, using dripping techniques, amongst others, placing the artist’s painting body at the centre. However, this painting body – which also brings to mind Yves Klein – came to transform or at the very least soil, deform, damage the very image of the body. This echo chamber of the image is the hallmark of her work.3

Fuses, her iconic 1965 film which is the first self-shot film expressing the erotic act of love making through the perspective of a woman, was reworked in a rich variety of ways: the film is blown up, printed, painted, covered in acid, coloured. That work was the starting point for a series of ‘paintings’ created according to a recurrent principle that she established then: the images are juxtaposed to create a sort of narrative, then adapted, stuck back together and painted over. The narrative perspective aims to be neutral, without judgement. The action is seen from the perspective of her cat, who watches the artist and her partner of the time, James Tenney. She presents us with a free body, liberated from the taboos of her time. With this work, Carolee Schneemann broke the chains that bound the body, particularly the female body. Fuses is a central piece as it draws together all the themes found in Schneemann’s work. It is both a starting point and a manifesto.

The images that Carolee Schneemann used in her installations and her collages came in part from the documentation of her performances. As the daughter of a doctor, of whom she said that he tended as much to living bodies as to dead ones, she used her own image as well as images from medical documentation.

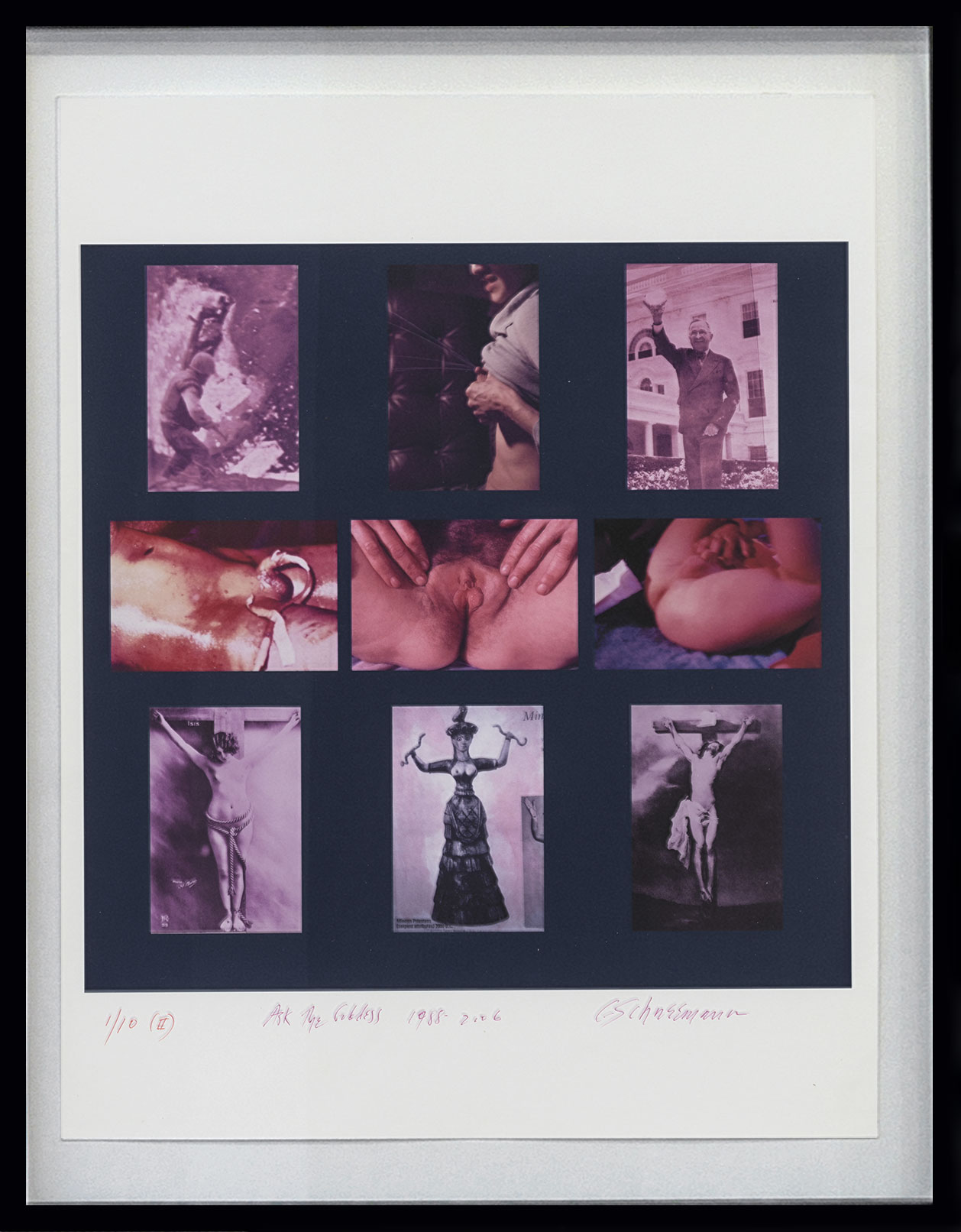

She also took images from various scientific and historical sources, such as in Ask The Goddess II (1988-2006) where a diversity of visions of female and male genitalia from history, mythology and fiction sit side by side.

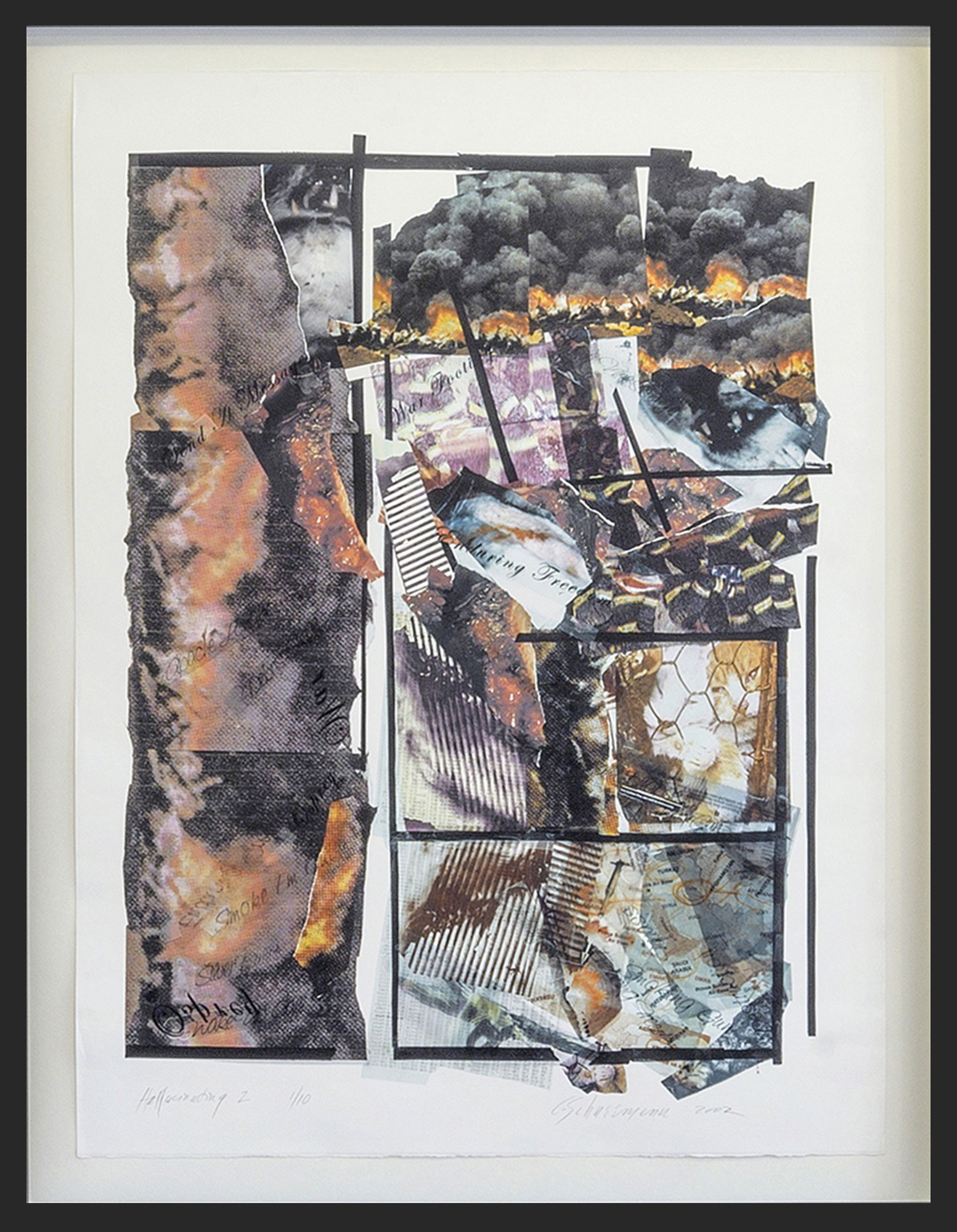

In the Hallucinating series (2002), she also uses war images, duplicated, cut and glued end-to-end to give an impression of deflagration. In Hallucinating II and Hallucinating III, we can clearly see images of the September 11, 2001 attack, including the body of a person throwing himself into the void and falling in front of the towers. These press images, which Carolee Schneemann collected in various media, are those used previously in a tribute work entitled Terminal Velocity (2001). In this work, Schneemann uses images that she enlarges and zooms in, then sticks and repeats, a principle that she will then develop throughout her work. This technique of editing and zooming can be related to his 1965 film Viet Flakes, which also deals with a historical and wartime fact, that of the Vietnam War. In these two works, Viet Flakes and Terminal Velocity, a deconstruction of time takes place. The sound collage made by James Tenney for Viet Flakes and the discontinuous fall of bodies in Terminal Velocity, suspend time. Also, how can we not see a possible reference to the Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp, which by superimposing the same image, prevents movement and makes the descent/fall suspended... Schneemann (Viet Flakes and Terminal Velocity), as well as Goya (The Disasters of War, 1810 - 1915) have, as a result of a current war event, created a work of art, a work of history

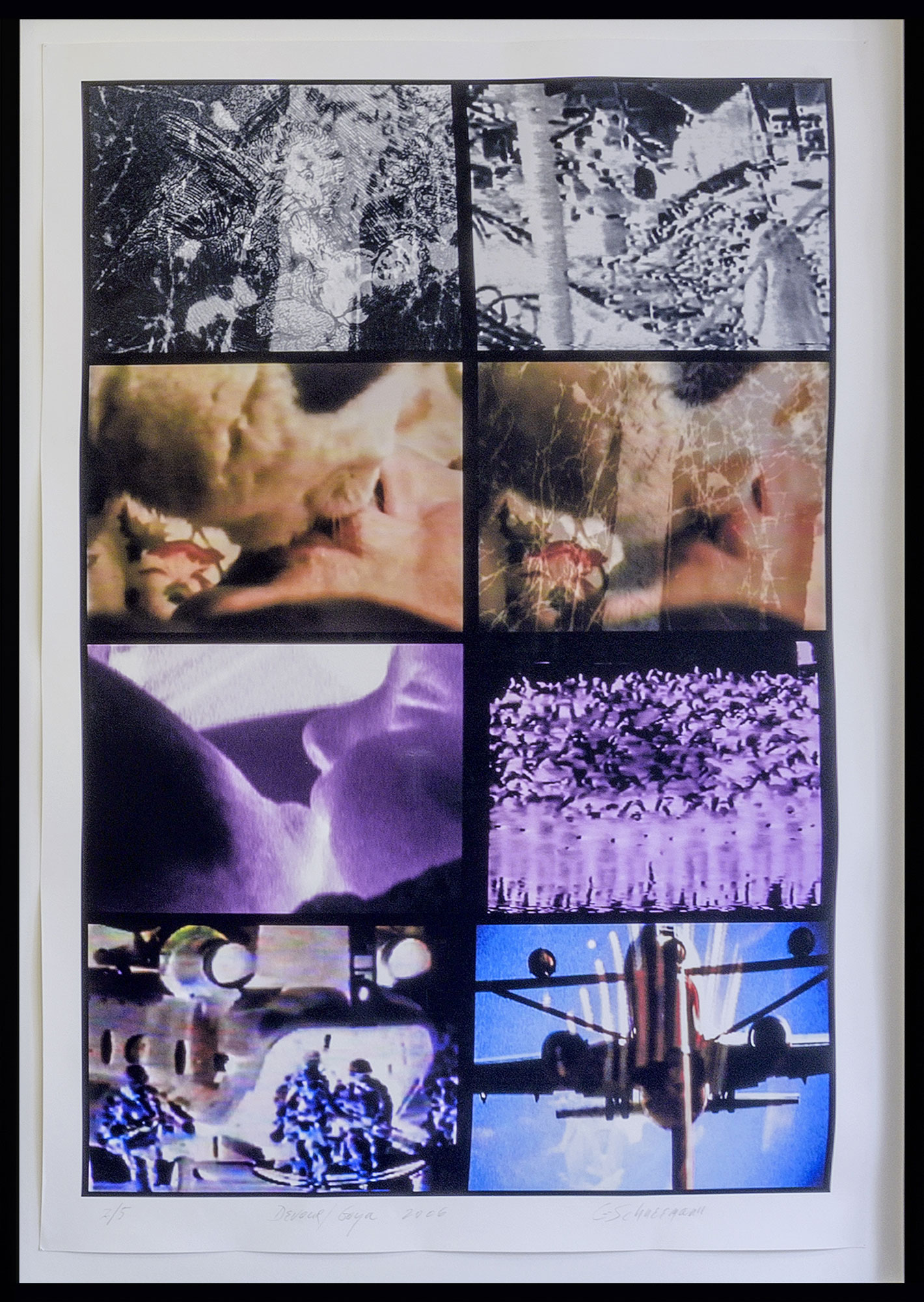

Working the same way as Robert Rauschenberg, who she met while at the Judson Dance Theater, Carolee Schneemann assembled a variety of fragmented images, which she then coloured and marked with her body. Just as Fuses was a film that inspired her paintings, Devour/Goya (2006) was originally a video installation projected onto several screens, a collage of images that were then modified, using a variety of media that respond to and complete each other. In this dense montage, the title means both the voracious (Saturn Devouring His Son in 1823 and The Disasters of War in 1810-1815 by Goya) head-on rush of contemporary media, and the corresponding, near-addictive impulse of its consumers.

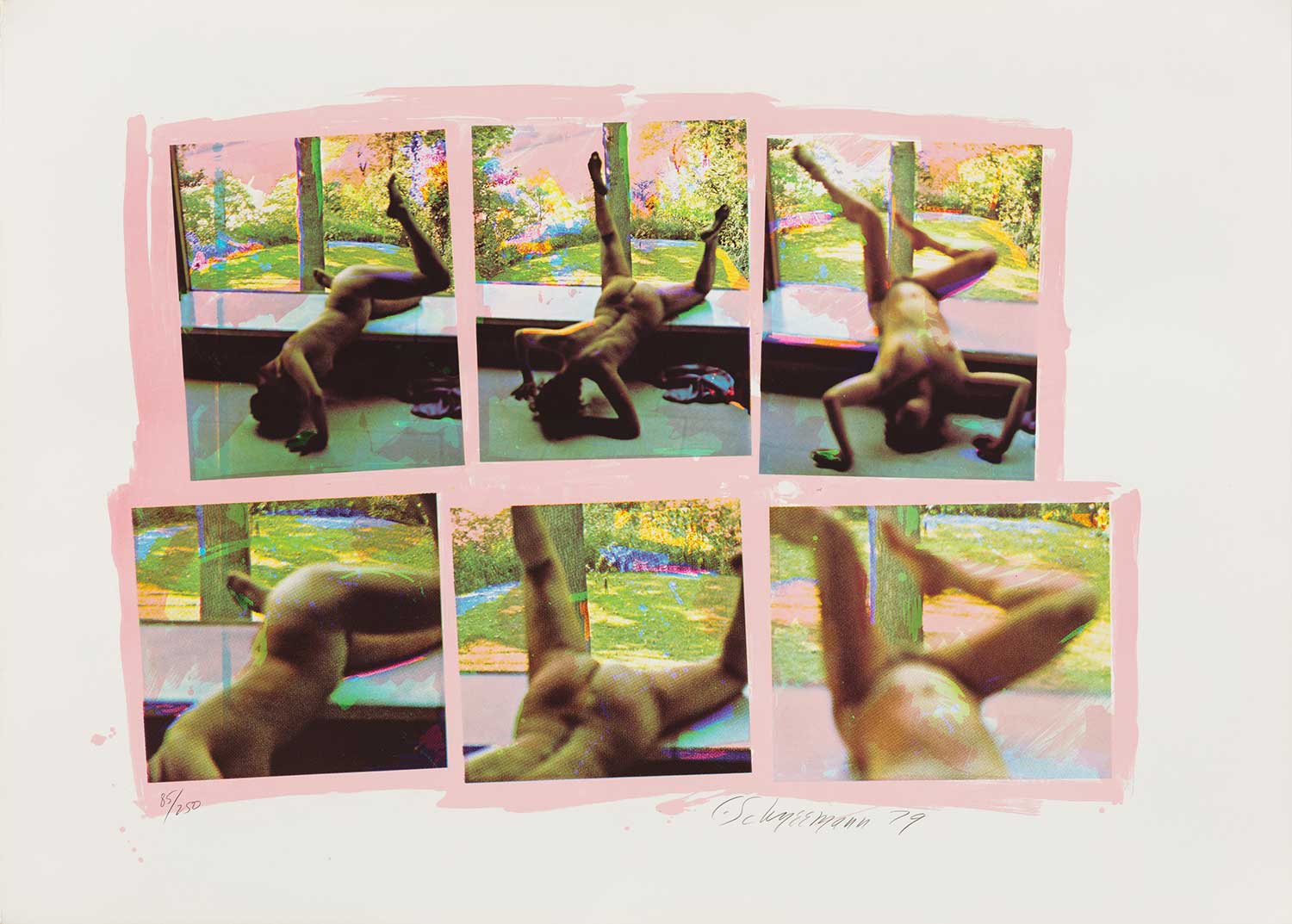

Her work Forbidden Actions - Museum Window (1979), reproduces six photographic documents of a guerilla performance at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands. In the museum galleries, Schneemann waited for the attendants to change shifts and quickly disrobed for a series of nude actions. Schneemann describes this project as an effort "to take the nude off the wall, in a way to de-sacrilize or re-consecrate this iconography…"

Carolee Schneemann’s adaptability to different surfaces means that her work retains the relevance of its beginnings: beyond her status as a feminist performance pioneer, she managed to break through to inspire our thinking on sequential narration, painting and cinema.

1. Carolee Schneemann, Imaging her erotics, MIT Press, 2002 : "As a painter I had never accepted the visual and tactile taboos concerning specific parts of the body".

2. Carolee Schneemann's artist book, Cezanne, She was a Great Painter, three editions in 1974, 1975 and 1976

3. Carolee Schneemann, “Radicalize Your Own Images and Sensations, Carolee Schneemann and heide Hatry in conversation with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve”, The Brooklyn Rail, 2013. "I have always written about the physical demands of perception and the visceral energy of painting—from nature, from closely observing the strokes of paint creating an image, the energy of abstract expressionism—all has lead to the actualization of perceptual energy.

Exhibition from September 13 to November 9, 2019

Opening on September 12, from 6pm to 9pm

At 7.30pm during the opening: conference by Emilie Bouvard

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) was a painter... as well! Throughout her career, she constantly reminded us that performances, films, photographs, texts were extensions of her paintings. The striking omnipresence of the female nude throughout her work was the better to elude the taboos of the time: “As a painter, I had never accepted the visual and tactile taboos surrounding specific parts of the body”1. By using her body as material, Carolee Schneemann reclaimed the female nude: far from the objectification of the nude present in classical art, Schneemann’s body was a subject, defiant, irrepressible and confrontational. She was a feminist trailblazer who used her body as a tool for advocacy, thereby distancing herself from the traditional representation of a model. The question Carolee Schneemann asks is whether the female body can be both an image and an image-maker, in a world where role models were scarce: "I decided a painter named 'Cezanne' would be my mascot: I would assume Cezanne was unquestionably a woman — after all the 'anne' in it was feminine. Were the bathers I studied in reproduction so awkward because painted by a woman? But 'she' was famous and respected. If Cezanne could do it, I could do it."2

As well as pushing the body beyond its limits, the images produced by Scheemann in her films, photographs or performances were later transformed through painting. Breaking with centuries of art history, her painting modifies the image rather than creating it. As such, she is positioning herself in the continuation of the abstract expressionist movement, using dripping techniques, amongst others, placing the artist’s painting body at the centre. However, this painting body – which also brings to mind Yves Klein – came to transform or at the very least soil, deform, damage the very image of the body. This echo chamber of the image is the hallmark of her work.3

Fuses, her iconic 1965 film which is the first self-shot film expressing the erotic act of love making through the perspective of a woman, was reworked in a rich variety of ways: the film is blown up, printed, painted, covered in acid, coloured. That work was the starting point for a series of ‘paintings’ created according to a recurrent principle that she established then: the images are juxtaposed to create a sort of narrative, then adapted, stuck back together and painted over. The narrative perspective aims to be neutral, without judgement. The action is seen from the perspective of her cat, who watches the artist and her partner of the time, James Tenney. She presents us with a free body, liberated from the taboos of her time. With this work, Carolee Schneemann broke the chains that bound the body, particularly the female body. Fuses is a central piece as it draws together all the themes found in Schneemann’s work. It is both a starting point and a manifesto.

The images that Carolee Schneemann used in her installations and her collages came in part from the documentation of her performances. As the daughter of a doctor, of whom she said that he tended as much to living bodies as to dead ones, she used her own image as well as images from medical documentation.

She also took images from various scientific and historical sources, such as in Ask The Goddess II (1988-2006) where a diversity of visions of female and male genitalia from history, mythology and fiction sit side by side.

In the Hallucinating series (2002), she also uses war images, duplicated, cut and glued end-to-end to give an impression of deflagration. In Hallucinating II and Hallucinating III, we can clearly see images of the September 11, 2001 attack, including the body of a person throwing himself into the void and falling in front of the towers. These press images, which Carolee Schneemann collected in various media, are those used previously in a tribute work entitled Terminal Velocity (2001). In this work, Schneemann uses images that she enlarges and zooms in, then sticks and repeats, a principle that she will then develop throughout her work. This technique of editing and zooming can be related to his 1965 film Viet Flakes, which also deals with a historical and wartime fact, that of the Vietnam War. In these two works, Viet Flakes and Terminal Velocity, a deconstruction of time takes place. The sound collage made by James Tenney for Viet Flakes and the discontinuous fall of bodies in Terminal Velocity, suspend time. Also, how can we not see a possible reference to the Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp, which by superimposing the same image, prevents movement and makes the descent/fall suspended... Schneemann (Viet Flakes and Terminal Velocity), as well as Goya (The Disasters of War, 1810 - 1915) have, as a result of a current war event, created a work of art, a work of history

Working the same way as Robert Rauschenberg, who she met while at the Judson Dance Theater, Carolee Schneemann assembled a variety of fragmented images, which she then coloured and marked with her body. Just as Fuses was a film that inspired her paintings, Devour/Goya (2006) was originally a video installation projected onto several screens, a collage of images that were then modified, using a variety of media that respond to and complete each other. In this dense montage, the title means both the voracious (Saturn Devouring His Son in 1823 and The Disasters of War in 1810-1815 by Goya) head-on rush of contemporary media, and the corresponding, near-addictive impulse of its consumers.

Her work Forbidden Actions - Museum Window (1979), reproduces six photographic documents of a guerilla performance at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands. In the museum galleries, Schneemann waited for the attendants to change shifts and quickly disrobed for a series of nude actions. Schneemann describes this project as an effort "to take the nude off the wall, in a way to de-sacrilize or re-consecrate this iconography…"

Carolee Schneemann’s adaptability to different surfaces means that her work retains the relevance of its beginnings: beyond her status as a feminist performance pioneer, she managed to break through to inspire our thinking on sequential narration, painting and cinema.

1. Carolee Schneemann, Imaging her erotics, MIT Press, 2002 : "As a painter I had never accepted the visual and tactile taboos concerning specific parts of the body".

2. Carolee Schneemann's artist book, Cezanne, She was a Great Painter, three editions in 1974, 1975 and 1976

3. Carolee Schneemann, “Radicalize Your Own Images and Sensations, Carolee Schneemann and heide Hatry in conversation with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve”, The Brooklyn Rail, 2013. "I have always written about the physical demands of perception and the visceral energy of painting—from nature, from closely observing the strokes of paint creating an image, the energy of abstract expressionism—all has lead to the actualization of perceptual energy.

Exposed artworks

Inkjet print on paper

21.65 x 16.93 in ( 55,5 x 43 cm )

Iris print

46.85 x 35.04 in ( 119 x 89 cm )

Inkjet print on paper

47.24 x 35.04 in ( 120 x 89 cm )

Iris print on paper

47.24 x 35.04 in ( 120 x 89 cm )

Inkjet print on paper

64.96 x 44.09 in ( 165 x 112 cm )

Inkjet print on paper

61.81 x 43.7 in ( 157 x 111,8 cm )

Frame: 65.75 x 47.64 in

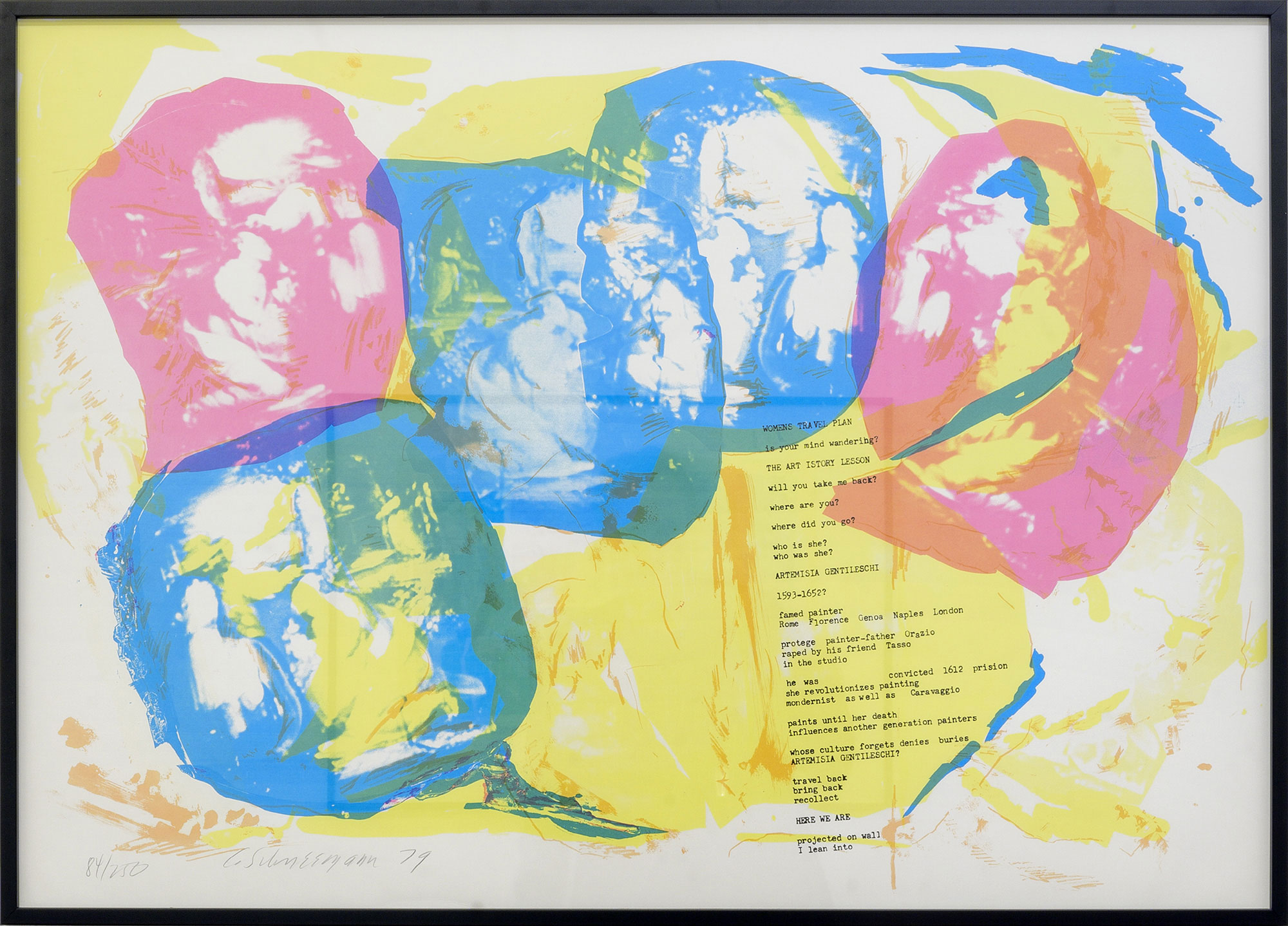

Photo-silkscreen on paper

30.31 x 42.52 in ( 77,5 x 108 cm )

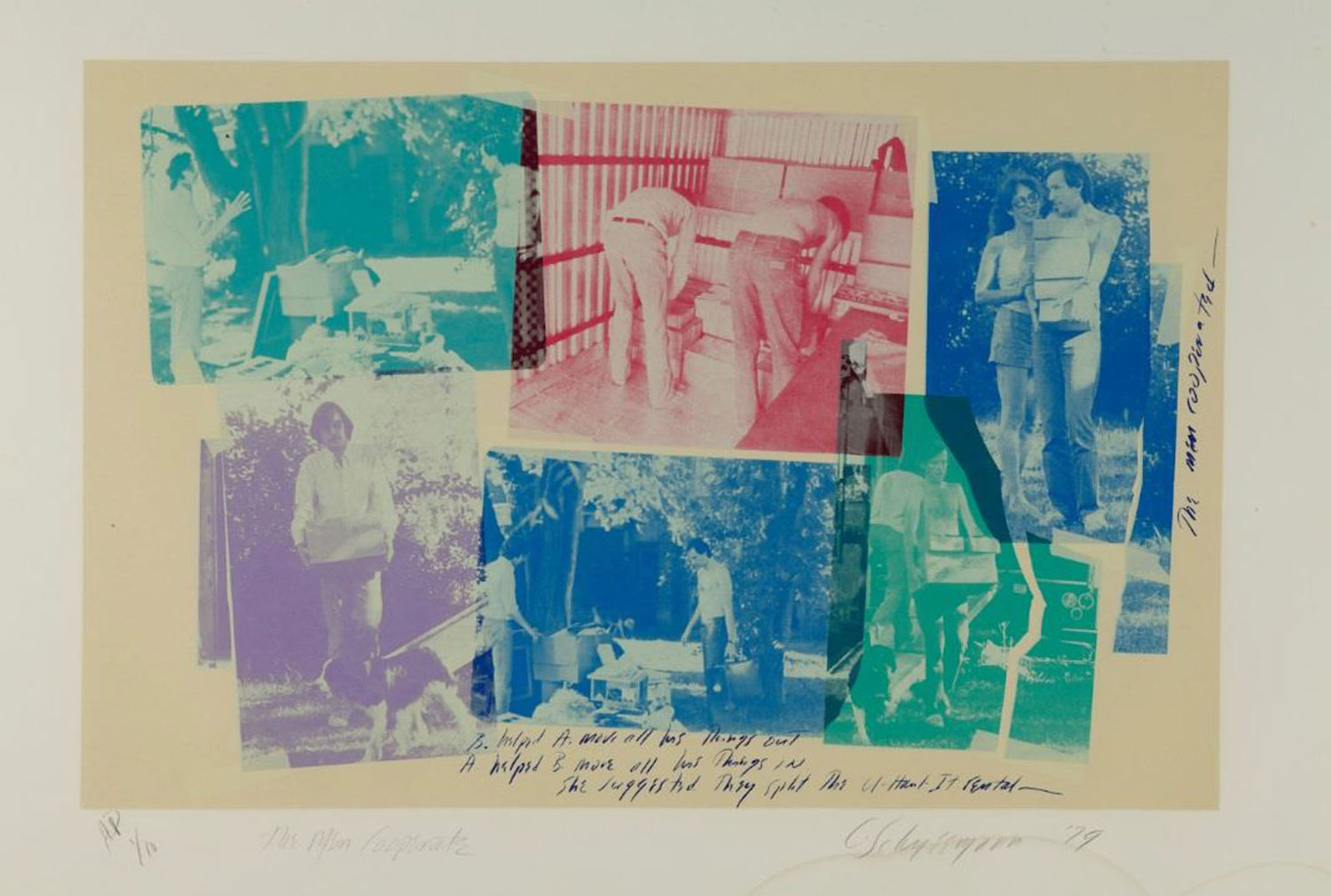

Photo-silkscreen on paper

29.92 x 42.13 in ( 76 x 107,5 cm )

Photo-silkscreen on paper

30.31 x 42.52 in ( 77 x 108 cm )