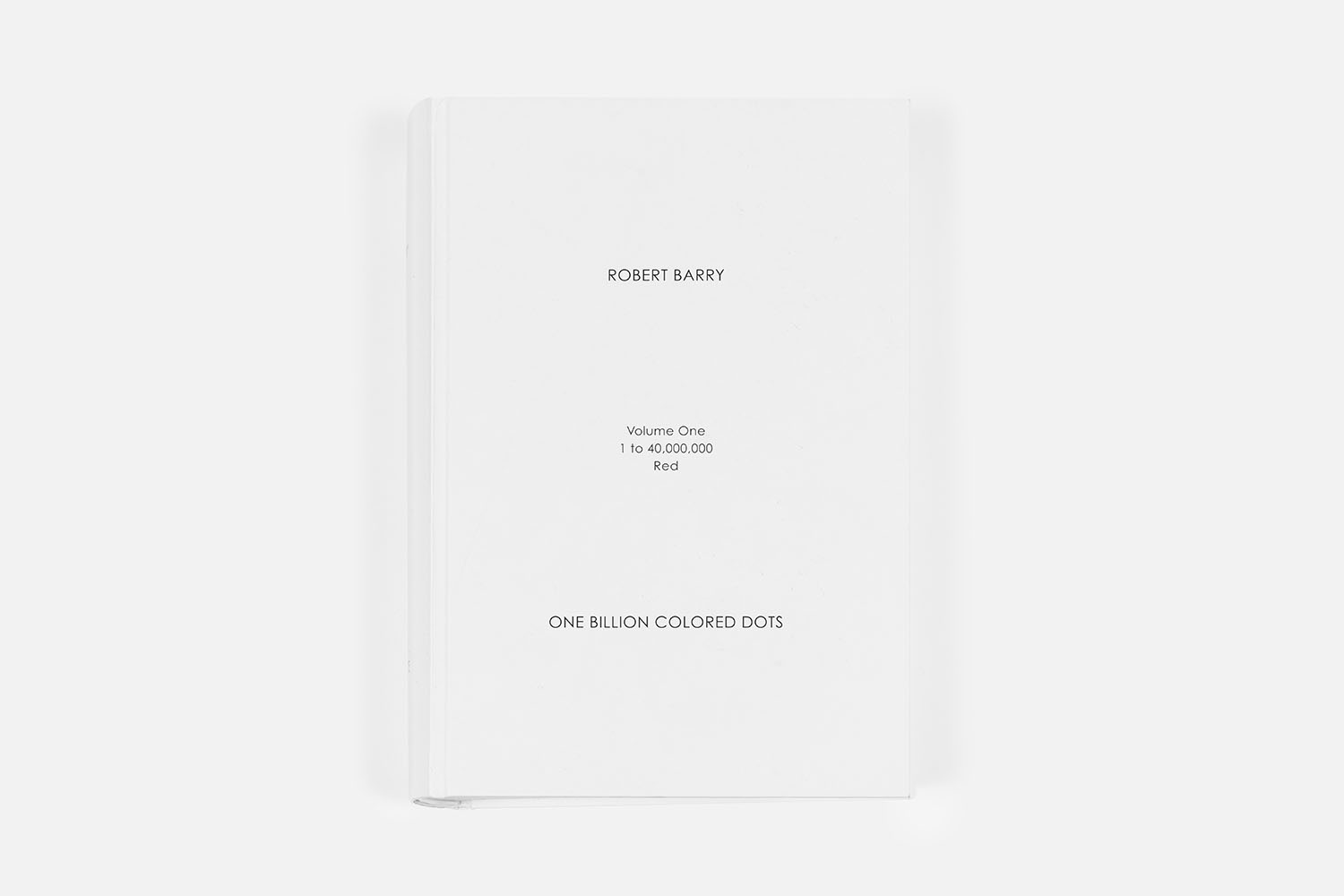

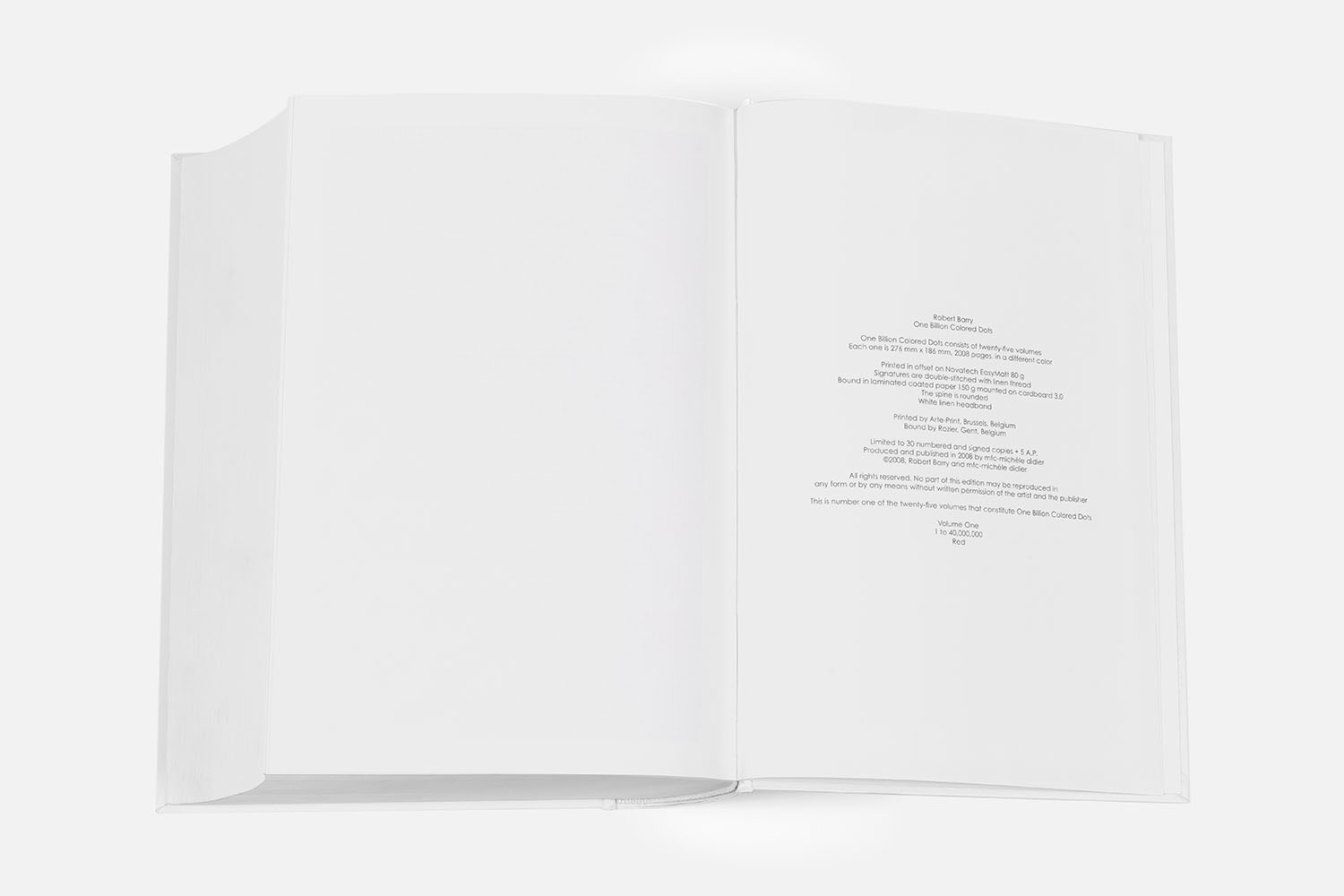

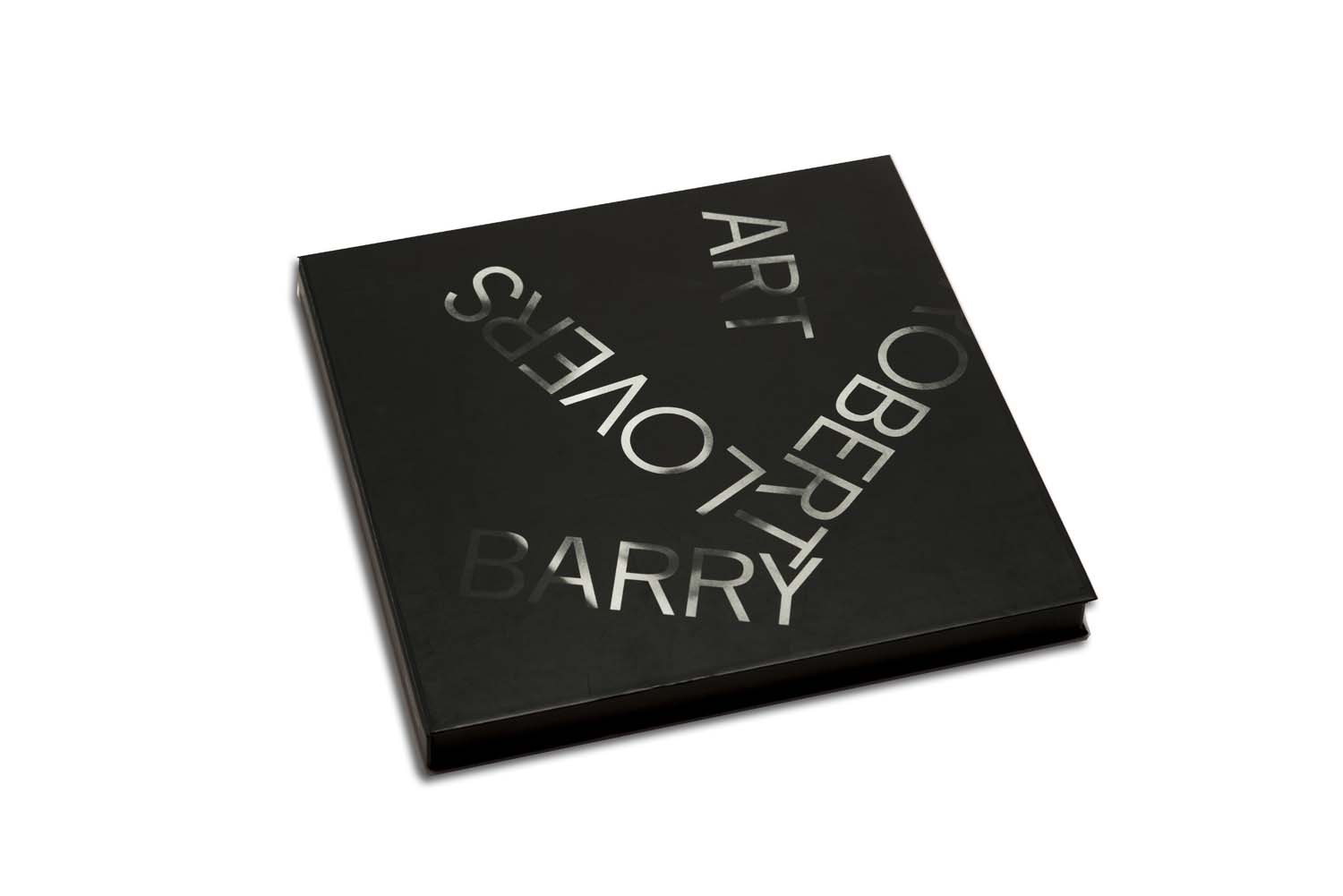

Robert Barry One Billion Colored Dots, 2008

Specifications

25 volumes, 27.6 x 18.6 cm, each 2008 pages

Total of 50,200 pages

Printed on recto only

Offset print on Novatech Easy Matt 80g

Signatures are double-stitched with linen thread.

Bound in laminated coated paper 150g mounted on cardboard 3.0

The spine is rounded.

White linen headband

Printed by Arte-Print

Bound by Rozier

Production

Limited to 30 numbered and signed copies and

5 artist's proofs

1968/2008

Produced and published by mfc-michèle didier in 2008

©2008 Robert Barry and mfc-michèle didier

NB: All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the artist and the publisher.

Selected public collections:

CNAP, Centre National des Arts Plastiques

FRAC Bretagne

Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Yale University Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library

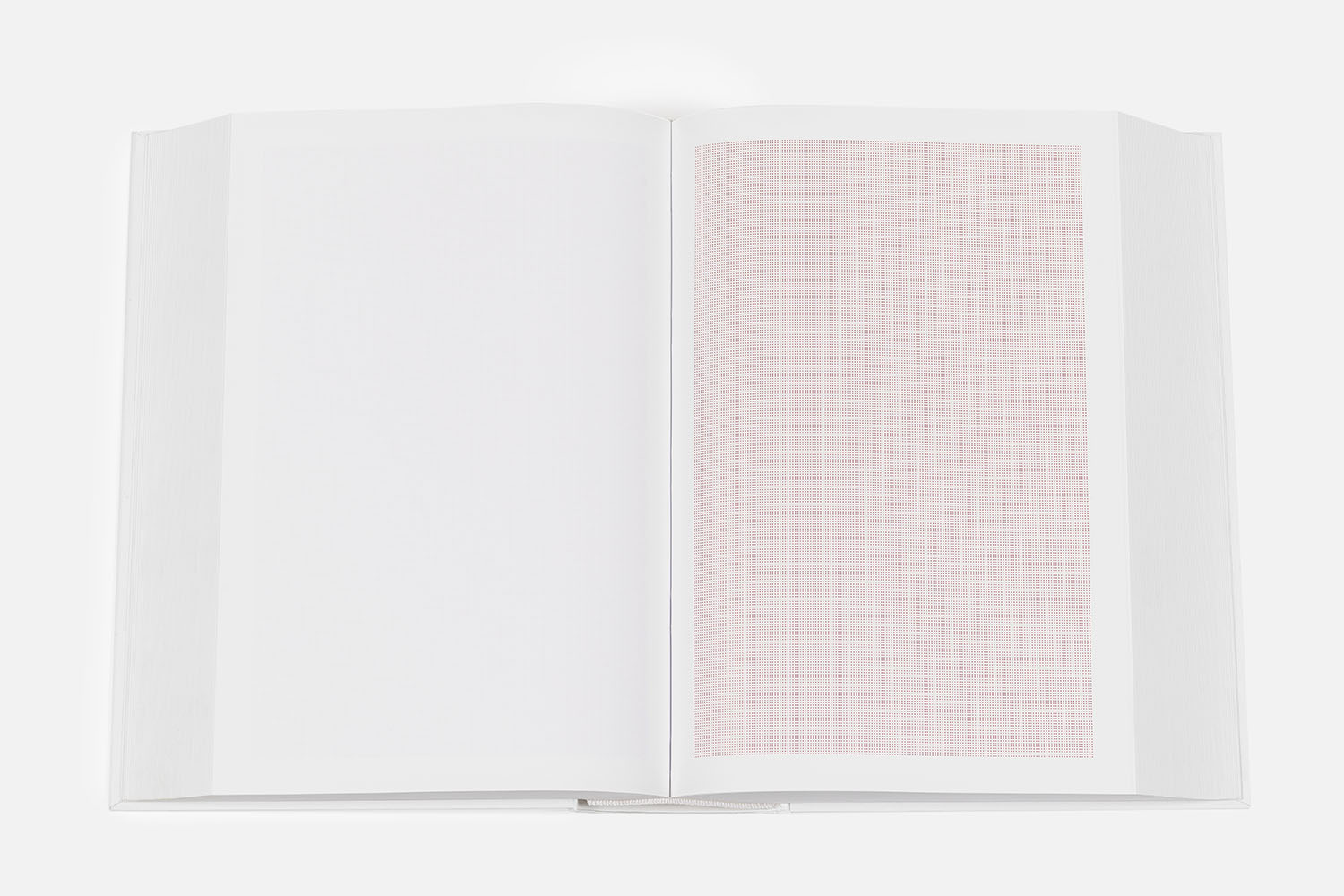

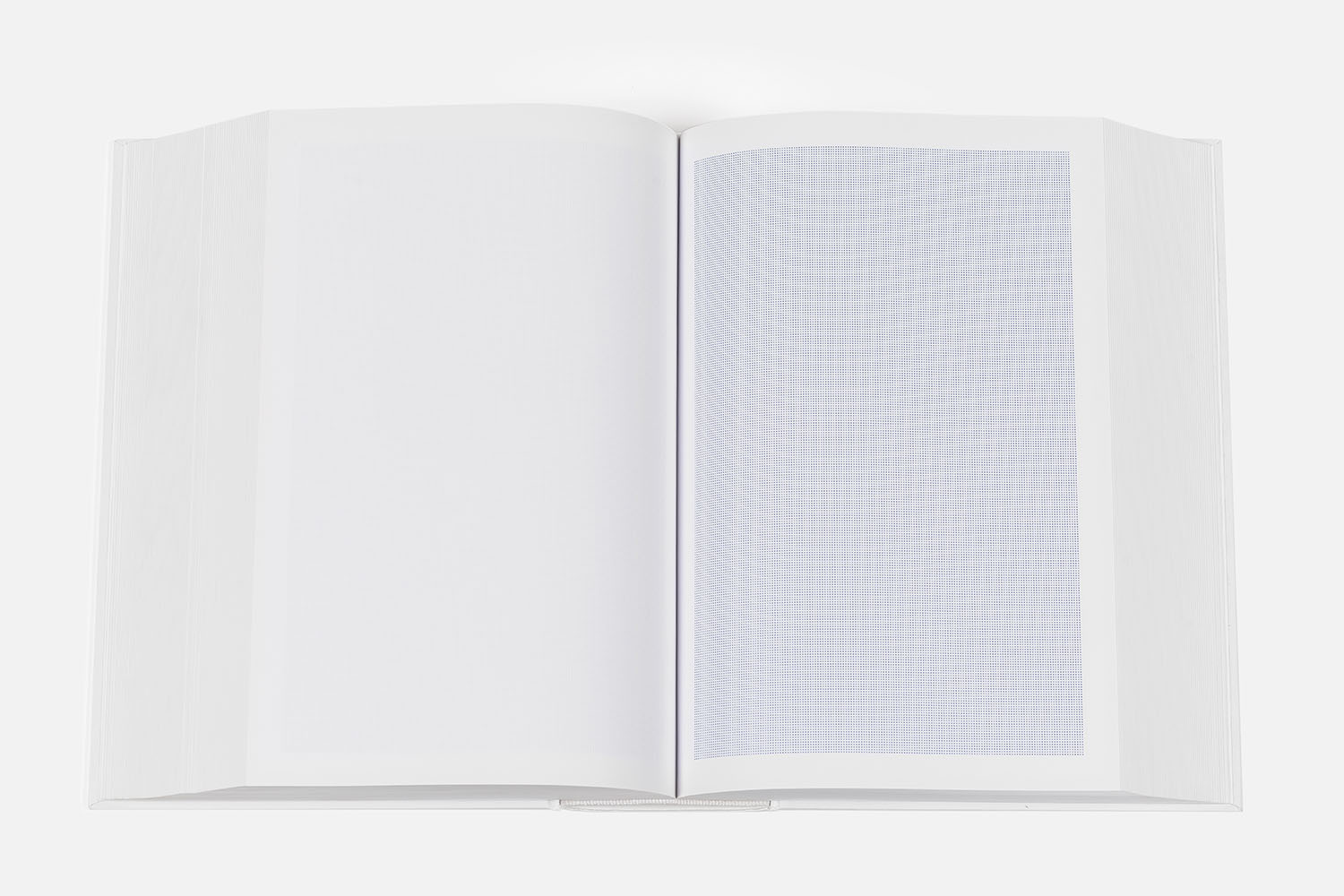

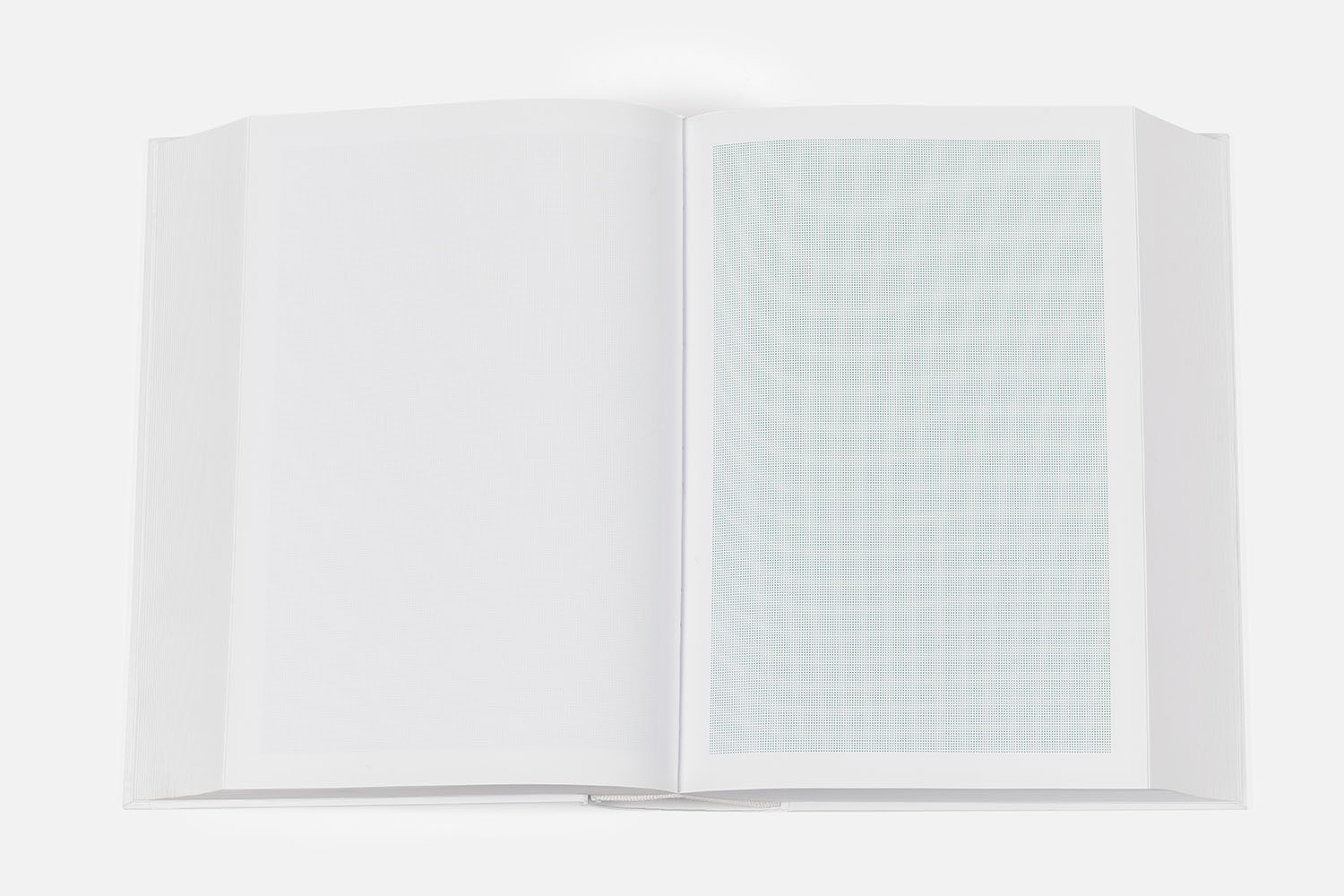

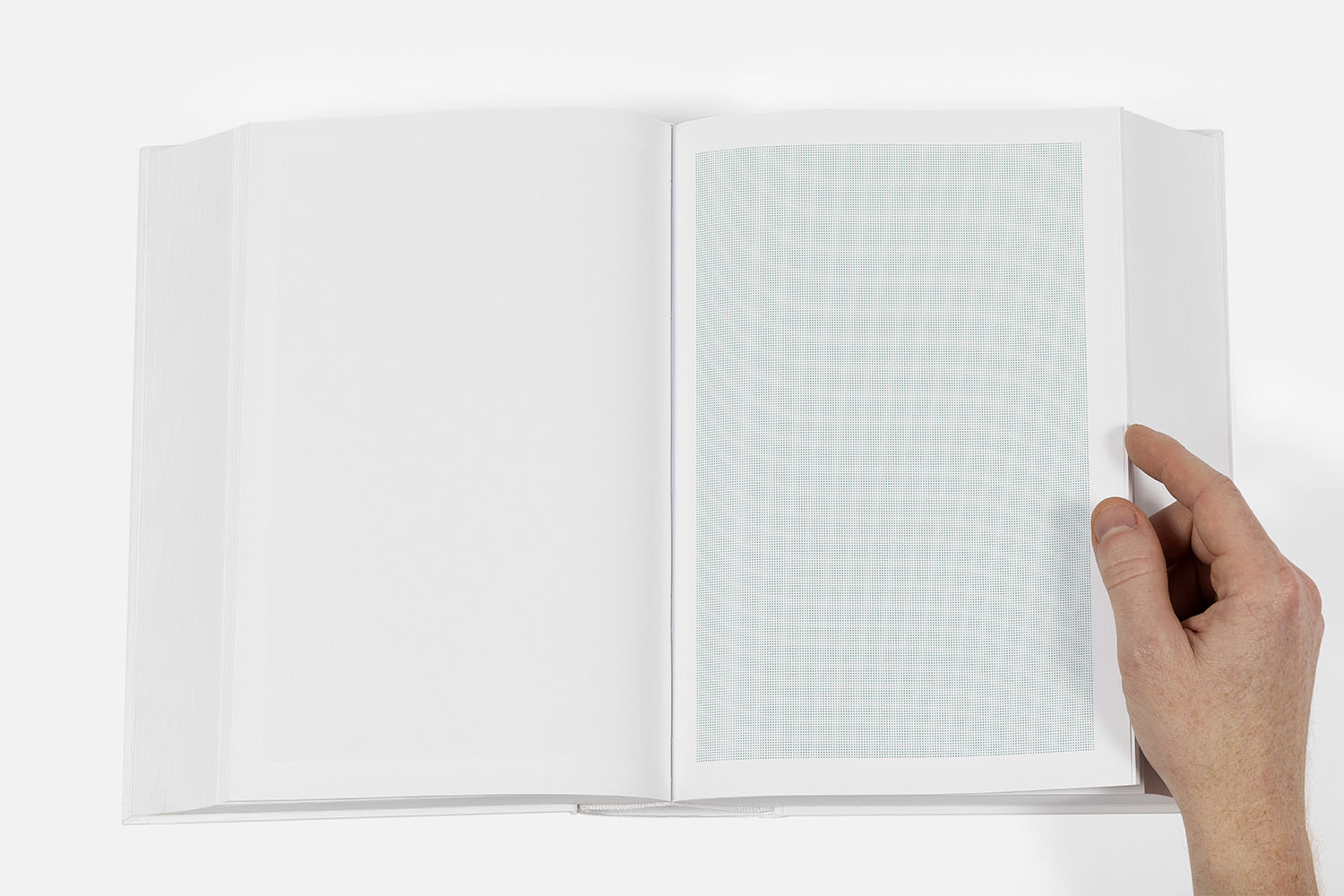

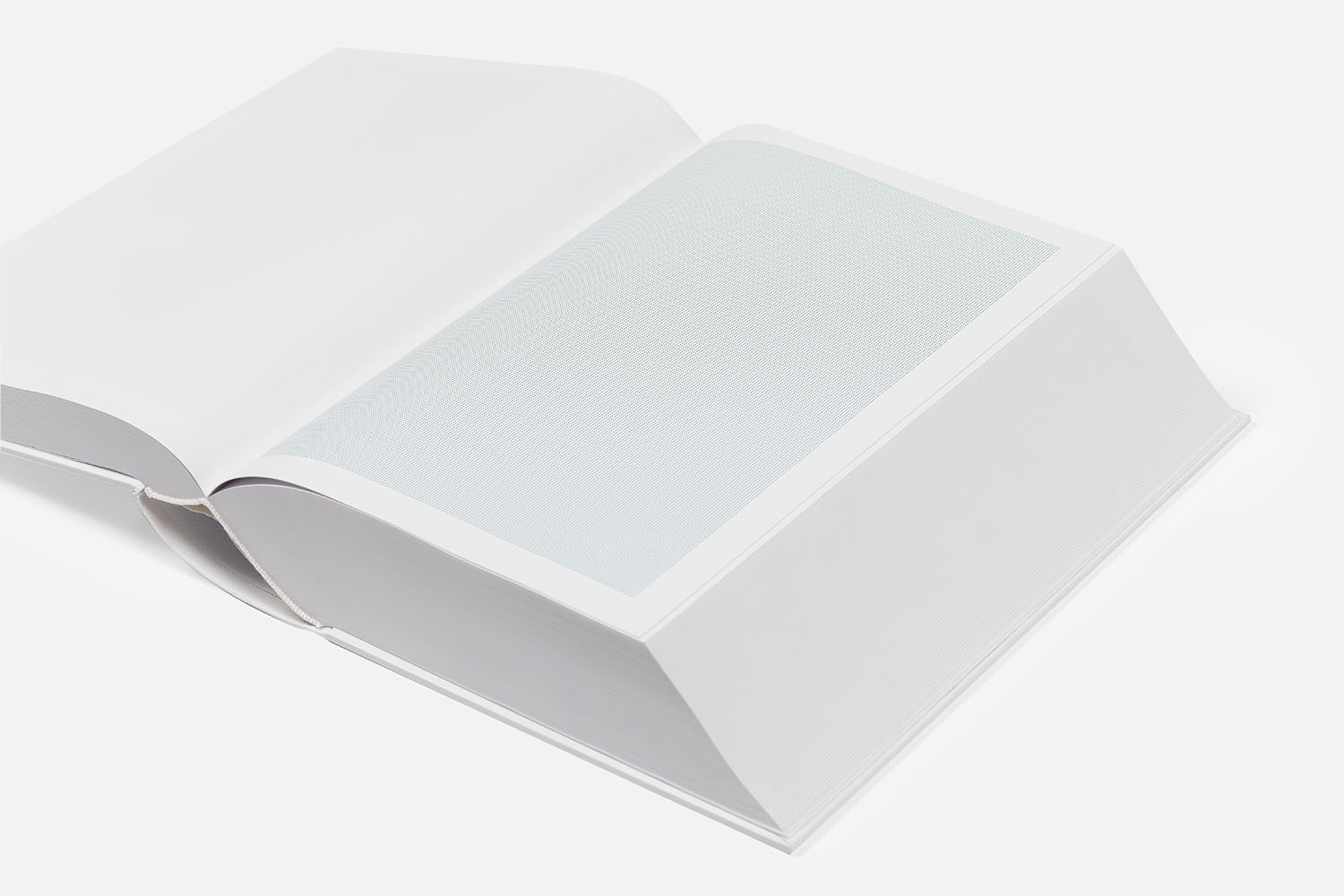

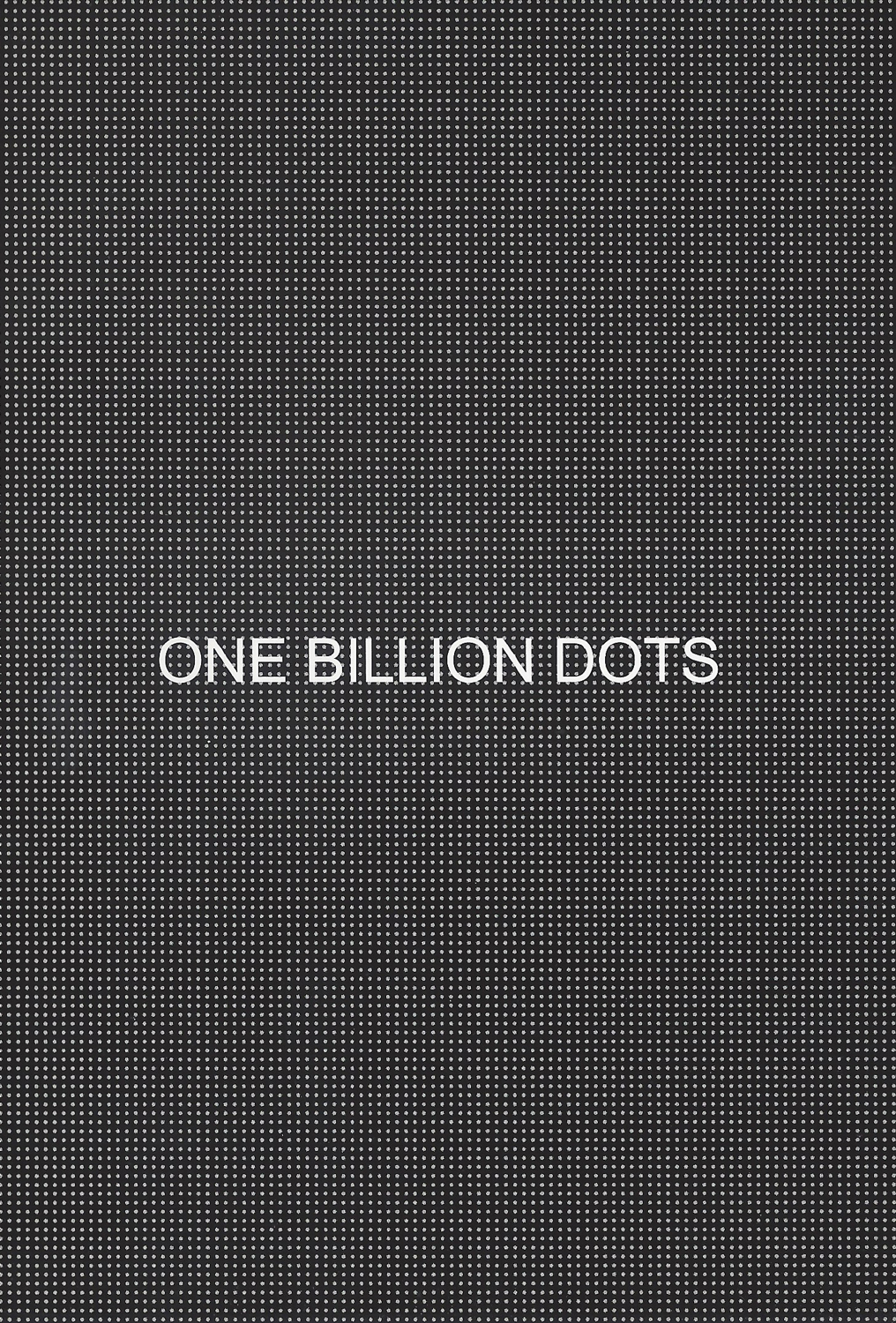

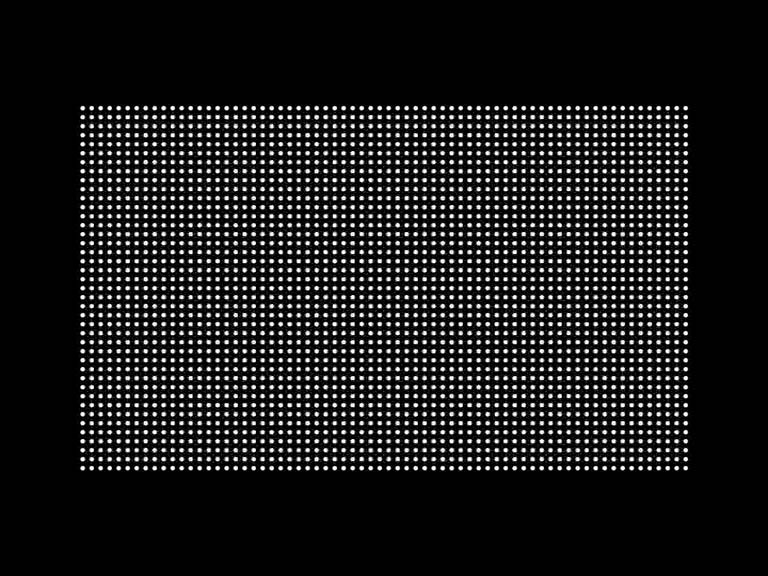

One Billion Colored Dots consists of 25 volumes and counts one billion colored dots at the rate of 40.000.000 dots per volume and 4.000 dots per page. The work is printed in as many colors as there are volumes: each volume has its own color. The accumulation of dots is oriented towards the edification of sense. Quantity constitutes the work.

I always do what I say I'm going to do1

Robert Barry, point by point

" He wandered amid stars gathered with the density of a treasure, in a world where nothing else, absolutely nothing else other than he, Fabien, and his comrade, was living. Like those thieves of legendary cities, walled up in the treasure chamber which they can no longer leave. Among icy gems, they wander, infinitely rich, but condemned. "

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry 2

" I always worked with quantity… the suggestion of extended space in my paintings, the inert gas pieces ("from measured volume to indefinite expansion "), half-lives with the radiation pieces, the radio wave pieces, etc. The idea of time, space, infinity, quantity beyond our ability to actually perceive or comprehend has always interested me. Even with Art Lovers, in maybe a more subtle way. I think it's always present in my work. "

Robert Barry 3

Time and space are the prime gauges of reality. Even if they are not its more tangible ingredients, they are the abscissae and the ordinates whereby the real occurs… or doesn't. " A very long time ago, there lived, in a wild and lonely forest on the Fulda estate4"... Thus starts E.T.A. Hoffmann's tale titled Ignaz Denner. To mention just one. For, faced with the issue that will more precisely concern us here, the rest doesn't much matter. The décor is set up and, for starters, the fact of knowing that the story took place sometime in the past is enough for the reader. What's more, he's not terribly bothered about the setting and the period, as long as they are indicated; it's the unlikelihood of the facts and the likelihood of their sequencing that will hold sway for the fan of fantastic narratives. Here he is, embarked upon a fantasy and confident in the vessel's seaworthiness. The minimum called for is guaranteed. Because it is actually first of all under the aegis of time and space that reality comes across, and make-believe is shored up by its example.

This is easy enough to go along with where space is concerned, because we can actually simultaneously experience two dots eight inches apart — even if we may have to very slightly squint or step back! Things are a bit more complicated where time is concerned, because two events twenty minutes apart can never be grasped concurrently, unless memory is brought into this operation — but memory does not help us to squint at these two events and put them together in order to contemplate them with the same comparative rigour ; the liaison made by memory is artificial : memory doesn't squint [Fr. loucher], memory is fishy [Fr. louche] !

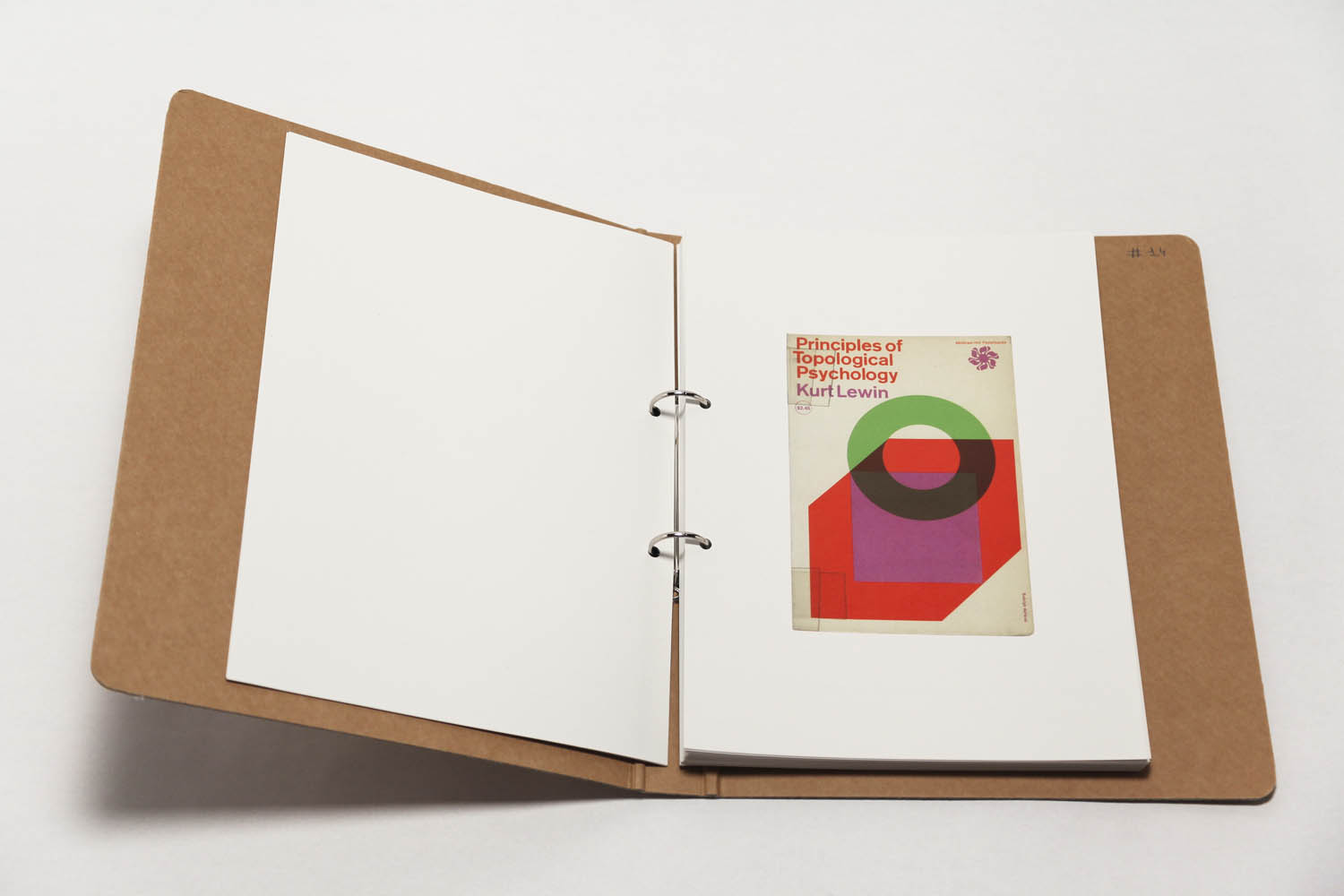

Three years elapsed between the moment when Robert Barry came up with the idea of lending a material aspect to the quantity — something abstract because of its enormity — lurking behind the number 1,000,000,000, and the execution in 1971 of this project in the form of a book in twenty-five volumes published in a single copy with the title One Billion Dots. Gian Enzo Sperone, the young Italian gallery owner and publisher who took up the challenge, has had some experience in this field. A powerful complicity already binds him to the artist, and to the so-called conceptual art scene's most adventurous, demanding and — to say it like it is — least sellable phenomena. Barry has already had two solo shows at Sperone's Turin gallery, and his first artist's book was published way back in 1970, a Sperone brainchild5.

The first show, in 1969, was one of a series of three, two of which were held simultaneously in December in Amsterdam and Turin, and the last, three months later in Los Angeles. Throughout these shows, the galleries involved were closed and their public was duly informed. We can imagine an event taking place in two places at the very same time, whereas it is harder to picture an event not taking place, but simultaneously, in two places. Simultaneity implies that the event has occurred. If it has not occurred, it has not occurred anywhere. The place where the event occurs thus lends it an evident existence. And if it occurs in two places at once, evidence of its existence is merely the more indubitable.

The three exhibitions, which were the first of what would be called the Closed Gallery Piece, did indeed take place, complete with venue and schedule. The event was turned into a non-event (or vice versa), but it counted as an exhibition. A sense of achievement can be found even in frustration! Because what was at issue here had nothing to do with any annoyance at finding the gallery's doors shut, until you pushed them to discover what was going on, because you happened to be in the neighbourhood. (Between two exhibitions, while they are being put up, opportunity inevitably recurred.) This time, it was no longer a matter of a gap in the programming. What was involved was a fully-fledged show. A show which counted, even retrospectively, as a symbolic act, like the basis of the artist's biography.

Robert Barry's second solo show with Sperone in Turin, in 1970, focused on the Marcuse Piece. The eponymous work consisted in a quotation from the American Marxist sociologist of German extraction, taken from An Essay on Liberation, published a year earlier. The quotation was composed for the occasion with adhesive letters on one of the gallery walls, people this time being allowed to venture inside, and spend a moment wondering what precisely they were doing there. This new proposition thus took the opposite position to the previous one. There was no frustration in the programme. On the contrary, the proposition was proffered this time around as a space of pure freedom and fulfilment. The highlighted quotation was, in this respect, in tune with the times: " Some place to which we can come and for a while ‘be free to think about what we are going to do'. " But what is left of the thinking of Herbert Marcuse, who was among the major ideologists of the revolutionary student movement of 1968? What is more, what need did Robert Barry feel to make reference to him, if we compare his quotation with the first rejoinder of the Interview Piece that the artist published in the catalogue for the exhibition Prospect 69, held in September and October 1969 at the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle: "The piece consists of the ideas that people will have from reading this interview7 "?

In 1969, as in 1970, at the Sperone gallery, the two shows consisted in just one work, and in each instance one idea formed the work. For the exhibition to take place, the idea must exist not only in the idea state, but as an artwork, too. No work, no show. Now the work, here, is not intended as the term of an art desire; on the contrary it is the commencement thereof. What interests Barry, and what interests us about him, is the art potential contained in the works. The work is an art vector. In it, art does not assume any definitive form that is carefully delimited by a peerless craftsman's expert hand, itself guided by the higher intelligence of a master thinker, but this work — with its impossible-to-follow outline and over which the hand will never be able to close, and in whose proximity the mind will never be at rest — is indispensable.

Closed Gallery Piece, Interview Piece, Marcuse Piece, with Barry. Duration Piece, Location Piece, Variable Piece, with Douglas Huebler. In spite of their concern not to clutter the world with useless objects, conceptual artists do produce a large number of works. The cultivated bourgeois and the expressionist painter, who both reproach them, terrorized, for skipping over them and hatching a plot aimed at precipitating the death of art, are utterly wrong. Conceptual artists are impatient. It is not their calling to be painters and sculptors, whose praxis would underpin the presumption that they are artists, would up that probability, and who might actually be just that, through talent, or by insisting thereupon. They are right away, and above all else, producers of art and, by the way things are, they are also producers of works. They are quite simply less concerned with producing art which pushes back art's boundaries — according to the modernist doxa — than with producing an art that alters our perception of the world and of artworks. It is art that must decide about the artwork, and not the other way round. "Art for me is making art8 ", Barry states. Bochner is more nuanced: " I do not make art, I do art9", where the use of the auxiliary tends to describe an attitude rather than an action. And Carl Andre adds the following confirmation: " Art is what we do, culture is what is done to us10 ".

Even if the gallery is closed, even if it is empty, the presumption of artwork is indispensable. With Huebler, the terminological shift is illuminating. Before long adopting the general idiom of Location Piece, he passingly used that of Site Sculpture Project in 1968. Even when immaterial, and reduced to the dimension of a project, the work must have the unimpeachable consistency of sculpture, as if it could more surely introduce itself as such, even merely by intent, into the world around us : as both an object and an act. But, instead, let us here consider the fact that the word "piece ", a simple copula added after a noun or a proper name, has the power to contest the most stubborn of situations — the closed door — and that it has the power to transform a closed gallery, an interview, a quotation, and so on, into so many experiences of a different kind, and into so many projects capable of freeing up as many experiences producing art.

And this is why three years can elapse between the expression of the project, as with One Billion Dots, and its completion — which cannot be seen as its depletion. Three years was also the time needed by Gian Enzo Sperone to collect the money needed to be able to put together, print, and forwarding his original edition. For if Barry's two shows, which he had just put on in Turin, had incurred almost no production costs, twenty-five bound volumes of more than 2,000 pages each (each sheet printed on just one side) is some investment! Luckily, the Cologne-based dealer Paul Maenz was interested in the book, and lost no time in buying it, before handing it on to Dr. Friedrich E. Rentschler (F.E.R.), in whose hands it still is.

Meanwhile, Barry was anything but idle. In 1968, he took part, in particular, in a group show in a higher educational establishment for girls, which was the last place anyone would have thought of as becoming a hub of contemporary art, had Douglas Huebler not happened to have taught there: Bradford Junior College, in Bradford, Massachusetts. Then, with this latter and others, Barry became the almost permanent guest of the leading incubator of Conceptual Art, Seth Sieglaub11, who, in January 1969, and then in March of the same year, and between July and September, too, organized in New York a series of confidential but historically decisive exhibitions.

It was in association with Jack Wendler that, from 1968 on, Siegelaub helped Barry to produce an initial approach to One Billion Dots, which is of special interest to us here. In the book Carl Andre / Robert Barry / Douglas Huebler / Joseph Kosuth / Sol LeWitt / Robert Morris / Lawrence Wiener published in December in en edition of 1,000 in the form of photocopies (whence the subtitle "Xerox Book" used for it), his One Million Dots does in fact already feature, with 40,000 dots per page, and taking up all the 25 pages made available to each artist by the publishers.

Between March and July 1969, an extremely productive period, as we have just seen, the student Patricia Norvell conducted a series of interviews published more than 30 years later in a book that has become a must read, and from which we have already borrowed material on several occasions. The list of artists and leading figures questioned, drawn up on the advice of Robert Morris, Norvell's profressor, is impressive: Barry, Huebler, Kaltenbach, LeWitt, Morris (needless to say), Oppenheim, Siegelaub, Smithson, and Weiner. The sum total is already so invigorating that it was hard to think it would be enriched by other appointments — sadly not kept! — with Carl Andre, Jack Burnham, Dan Graham, Eva Hesse, Lucy Lippard, Richard Serra, and one or two others... Siegelaub answered the student's questions on 17 April 1969. We know all about the many different projects he was involved in at that time and, as if that wasn't enough, he pointed out: "I have a gallery, for lack of a better word, called the Gallery in California now12 ". Siegelaub and Barry would not go to Los Angeles in April 1969, but the latter nevertheless had a solo show in the aforementioned gallery. If the truth be told, the exhibition only existed as an item of information. Barry had gone to California the month before. There he had come by several bottles of rare gas, to be emptied in six places. A poster was published later and sent out to a highly targeted mailing list announcing the April show, but nothing was ever shown. And all that exists of his Californian activities is some photos of landscapes, certificates and inert gas molecules which have roamed around in the atmosphere ever since, altogether harmlessly13. The gallery was useful for spreading information. The programme went ahead. The exhibition was proof thereof. Siegelaub and Barry were indeed involved in it together, but they became tired of exhibitions promising lots of things to see where, in their eyes, nothing came to pass.

Accumulation, dissemination, you will hopefully please forgive me for this lengthy detour, but the parallel between the inert gas series and that of the million and billion dots seems natural. To be freed from the atmosphere, and to be ‘returned' to it, to borrow Barry's term, rare gases must first have been artificially captured like Duchamp's glass ampoule filled with Paris air, or like Piero Manzoni's can of artist's shit) and kept in tanks. And their dissemination is aimed at nothing other than a rarefaction of rare gases. We can see an ecological gesture in this return to the atmosphere, but we should above all consider in it the failure of our temptation to put everything in order by way of thought and acts. Releasing a rare gas into the atmosphere, where it is naturally present in infinitesimal amounts, it is tantamount to undoing the task of capturing and packaging it, as carried out earlier. Any aspiration to purity must thus slip between our fingers. With the rare gas that escapes, it is also the notion of given volume that vanishes. Now, purity is only quantitative: 100% of concentration equals 0% of foreign body14.

And so it is the reverse approach that Barry follows by focusing on One Million Dots in the 25 pages of the Xerox Book earmarked for him, then by multiplying by one thousand this operation in the 25 volumes of the One Billion Dots, and finally, all of 40 years later, in the other 25 volumes of the One Billion Colored Dots, this time around published by the French publisher Michèle Didier, based in Brussels. Each dot is insignificant, but it is the sheer quantity of dots that here gives a measure and a meaning to the undertaking. The accumulation of dots is oriented towards the edification of sense. And it is, conversely, dispersal that played this role in the inert gas series15. Inert gases and dots alike, the quantity thereof, overdetermined in both instances, all links up with the function of the word "piece", as referred to above. Quantity constitutes the work. The quantity of works, too, incidentally. So, eager to reduce to a strict minimum the documentation surrounding and illustrating his actions, Barry explains that a work may only be rendered more explicit in the context of a series than in an isolated way. Because there are six inert gases in the last column of Mendeleyev's periodic table, the programme is all laid out. The works Telepathic Piece and Inert Gas Series are art vectors and the words "piece " and "series " are identifiers, markers and tracers. The art object may be becoming more and more discreet, and may even be vanishing altogether from people's concerns, but art is still the ultimate goal. Conceptual Art has been seen by some as a lethal threat, but have people asked themselves if there was ever a keener desire for art in history?

All the artists in Siegelaub's entourage were painters before going on to other things. Douglas Huebler and Robert Barry, too. So this is not why they had a closer relationship. The reason is that they both taught and because they both had families. Which reduced their mobility. Besides, Barry tried to land a job in New York for Huebler at Hunter College, where he himself taught after studying there, but he failed to lure his friend to the City University of New York, to which Hunter College belongs — and we know that Huebler no longer lived or worked in New York after 1953.

Douglas Huebler acknowledged the influence of oriental philosophies on his own change of course. And it was probably the graphic works he produced between 1968 and 1976 that were the most marked by them. All sorts of archival documents, handwritten and typed alike, are pigeonholed in the " graphic works " category. The ones I want to talk about consist in blank sheets of paper with captions at the bottom in a style that calls to mind Lichtenstein's aphorisms. Let us give an example: " The surface above reflects an indeterminate amount of light when this book is open to these pages but is absolutely non-reflective when the book is closed ". In other such captioned "drawings ", an isolated dot may be centred17 or dots may be distributed evenly over the surface. To summon onlookers to a special perceptive and existential experience, the artist invites them to stare closely at the flawless surface, or at the isolated dot, or at the series of dots.

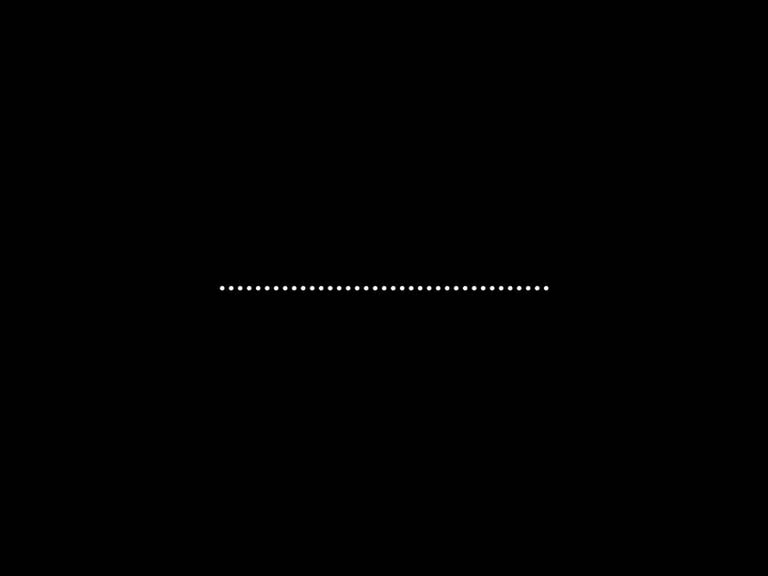

Barry, for his part, fills whole books with dots, and their quantity is such that he lets us get away with not looking at them all. Together with the publication of the One Billion Colored Dots, in 2008, Michèle Didier published a digital, monochrome version of One Billion Dots, composed differently from the original printed version, and designed for video projection. In this form, the experiment took 4.153043981 days, that is, 99.6730555 hours, that is, 5,980.383333 minutes, which works out at 358,823 seconds18. Is it then possible to imagine how many works of literature would have to be compiled to reach the grand total of one billion dots that Robert Barry was after? Four days spent without taking breath at the end of every sentence — nobody could survive that! Let us leave Remembrance of Things Past aside, even if the title is a programmatic one, because, given the length of Proust's sentences, full stops are too rare in his writing...

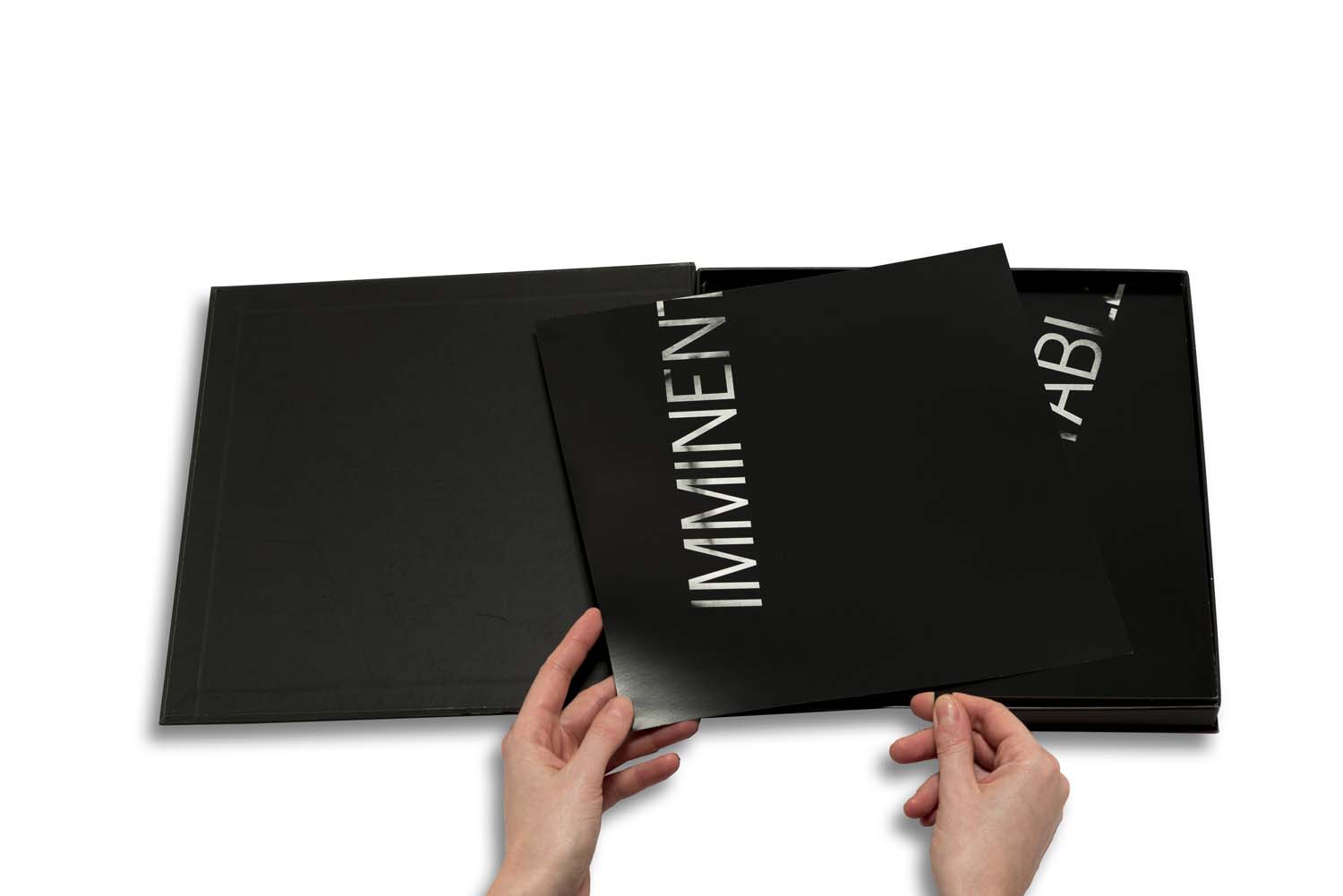

What kind of readers are we when we peruse the 25 volumes of One Billion Colored Dots? Does experience result from reading? Certainly not. It assumes an appearance thereof because a book is involved, but this book does not contain any information, except on the title page and at the end of each book on the page containing the colophon. And no imagery is disguised in these expanses of dots, even if all you would have to do is link up some of them, in a certain order, to bring out thousands of images! So regarded as a set of books, One Billion Colored Dots is empty. And regarded as a reservoir, it is full. Full, but content-less. For, as Sartre said: "Colours and forms are not signs, they refer to nothing that is outside them19 ". And we are faced with this sum like a person suffering from memory problems, before which, in a disorderly manner, process the guests at a reception held in his honour, and who, having for each guest a fair-minded word of welcome, would be unable to tell whom among his guests have already been introduced to him, and whom he still has to greet. To keep up appearances, these seriously ill people wear an occasional smile in society, but they are lost and confined in a profound loneliness. In front of Robert Barry's billion dots, we are lost, alone in front of the host and we flit from one volume to another, without either order or method, like the pilot in Saint-Exupéry's Vol de Nuit [Night Flight]. For it would be silly to start on page 1 and hope to end up one day on the 50,200th page. Just as it would be absurd to slip in a bookmark, promising to resume one's reading later, where one had left off. Robert Barry's accumulations of dots are part of a very specific category of books which exist in their own right, without it being necessary to open every page... if one has leafed through very superficially at least once.

The best conditions for presenting the One Billion Colored Dots are when the 25 volumes can be opened simultaneously on one and the same desk or similar surface, at a height where you can consult them standing up. The reader-cum-peruser can thus move freely about from right to left and left to right, from one colour to another, renewing associations as the mood takes him, with colour being allocated an unusual function that could not be assumed by Sperone's monochrome edition. Apart from the title page (bearing no mention of the date or any explanation of the edition on the latest publication, where these data and many more are included in detail in the colophon, at the end of each volume), the 25 volumes printed in 1971 were all identical.

The physical experience is complicated in the Michèle Didier edition by the very fact of colour, which prompts readers to leaf through the books, or at least jump from one to another. In 1971, the books could remain closed. In 2008, they must be used, i.e. handled. The colour must be revealed by light. For this is a different experience when you lean over a page peppered with blue and red dots. And further back in the process, the artist makes a specific experiment when he selects the colours and when he names them. Questioned about his choices, his answer was nevertheless laconic: " I wanted all the basic and secondary colors plus white, black, grey, gold, etc.20. " Asked about the principle of colour classification, he offered a painter's reply: " No system, just what I thought felt right21. " Which gives: n° of volume Pantone reference Subtitle given by the artist

1032red2293blue31505orange42685violet5334green6102yellow7228maroon

83262bluegreen9621lightgreen10110ochre112635lightpurple12541lightrey132955darkblue

14230pink15375yellowgreen162592purple17162lightorange182405redviolet19100lightyellow

20877*silver21290lightblue 22427grey 23871gold 24white*white25blackblack.

Why does Barry stick to such short answers? So as not to substitute his appreciation for that of the user, probably, who can note, all on his own:

that the artist has refrained from using primary colours;

that red and blue are the first colours of the series, but that yellow only appears in sixth position;

that black has been kept to the end;

that the white dots in the penultimate volume are invisible, printed on white paper, unless you bend down and look at the book askance in oblique light;

that gold and silver are black, conversely, if they are not looked at head on, in direct light;

that the dispersion of the printing in a host of dots creates a grid-like effec;

that certain, usually light, colours, like "light green', "light yellow" and "light blue ", lend the dot-filled pages a vibration that is hard to deal with a close quarters;

that the colour of the surfaces thus gridded is very diminished in relation to the colour of the dots taken separately;

that the grid more easily gives the illusion of a flat tint if you narrow your eyes;

that the nuance between certain colours, like the "light blue ", the "light green " and the "light grey " is never subtle enough to cause a muddle;

that from the "maroon " tallying with the bordeaux in volume seven to the "pink ", Barry seems to have a soft spot for shades of purple;

that the "maroon " is not a brown and the "purple " is not a purple;

that the "purple " does not exclude "violet ";

that the artist has preferred a bordeaux and an ochre to a mid-brown, which does not exist on his chart possibly because the mixture is too indecisive...

You can see enough things when you look closely at these books without having to wonder what you might be seeing in them. Yet the physical experience grapples with the semantic experience in the very moment when you observe them. And it can be noted, with some astonishment, that it is not possible to decide which is the most immediate, between the physical and the semantic. The word red probably has an intensity equivalent to that of the colour it is used to designate. Naming is tantamount to setting apart, it is tantamount to assisting facts in order to assimilate them. The fact is, visual experience is already mental before being verbalized.

For Sartre, "words are transparent and [...] the eye passes over them22 ". For Bochner, it is the opposite. Only "numbers are really transparent23. " On the other hand: "Language is not transparent24 ". For Sartre, words are transparent because they refer to something: the attention must not be fixed upon them. For Bochner, they cannot be transparent, because they are ill-suited to being referred back to a single objective: they redirect the thought which they are supposed to serve, and an essential part of the work of this leading conceptual artist, which escaped Siegelaub, is based on this opaqueness, where Barry readily links back up with him when he declares: "The use of language is very difficult. It's something which is not natural to me25 ". No words or so few in these 50,200 pages which, when bound, form books that are absolutely full or absolutely empty, as you will, but anything except transparent.

For Barry, more so than with a certain number of his contemporaries, the documentation attached to the work should not be presented as anything other than a proof of the work's existence, but the existence of the documentation has the drawback of being imposed in a too flagrantly obvious way in relation to an artistic intervention which has so little material existence. It has, it just so happens, the major original flaw of having to be attached to it. "There's no one who makes work quite like the way Barry does ", emphasizes Siegelaub. "Because he doesn't even have a piece of paper in the end to tell you. He doesn't even have a statement about something. When he's finished, he just has, you know, just the fact of having done it. It's his word that he did it at all. [...] Barry is quite a bit different. There's absolutely nothing26. "

The will to stick with the work itself, excluding any documentary or semiotic apparatus, calls to mind the demand for the artwork's plastic autonomy as claimed by earlier generations. And let us acknowledge that, as part of a Marxist-inspired approach27, veering towards the liquidation of the object and in passing) of a certain art market, the certificate which is part of the documentation is cumbersome as a title of ownership.

I came up against a wall when I asked Robert Barry to talk to me about his first two artist's books, that came before One Billion Dots. The first time I tried, mentioning their titles, the names of the editors and the publication dates, and only asking him what kind of books they were, he replied "artist[‘s] books, black text on white paper28 ". Too short, I thought. And I got back on the case by asking him to describe them for me. This is what he replied second time around: "No, not more than I have. How can you possibly know the work of art unless you have seen it? If they are important to your work you will have to find them. How do you know about them? When you see them you can ask questions. A description is incomplete and can be misleading29. "

Any comment can be to the advantage of the documentation, and thus to its disadvantage if the documentation is deemed problematic because it may shift the attention and cause a distraction in relation to the artist's intentions.

To point out a work — Barry and Siegelaub are not wrong here — just one reference to its existence in a list at the end of a catalogue suffices. In these conditions, needless to say, it is possible to sidestep it — the work — without noticing it, but because the essential thing is that it exists, is this not better than seeing and describing it while seriously misunderstanding what it is about? "Anything that one names is already no longer quite the same, it has lost its innocence. If you name the behaviour of an individual, you reveal his behaviour to him: [...] his furtive gesture [...] starts to exist in a big way, starts to exist for one and all, [...] it takes on new dimensions, it is retrieved30. " From my own point of view, I prefer, firstly, to do without commentary to discover an exhibition. All commentary is by nature intrusive and additional. The most suspect of commentaries, albeit additional, is certainly the one which claims only to be filled with the substance of the work it is talking about. The critical space either opens up or disappears completely — it depends — with Conceptual Art. For Barry, it evaporates. To the very relevant question: "What about the question of judgment, whether a piece is good or bad? ", raised by Patricia Norvell, he has a disarming and irrefutable response: "I don't even think that there'll be that judgment. I think that the whole definition of art will be changing. The thing just is. I mean, how can you criticize a carrier wave? How do you criticize inert gas ?31 " The work disappears as an object, but Robert Barry here amazingly reduces it to its material components. This is perhaps why he chooses components that are precisely almost immaterial: gas, numbers, and radio waves... But his contribution cannot be scaled down to a mere updating of the readymade.

Robert Barry is still steeped in the grid work which he undertook as a painter back in 1962 when he came up with One Million Dots and One Billion Dots. His first solo show, at the Westerly Gallery in New York, in 1964, was in a minimalist vein. In it he showed monochrome pictures whose square "motif " regularly repeated was presented in the negative like a blank in a coloured flat tint. The following year he took part in a group show in the same venue. In it, Lawrence Weiner noticed one of his drawings and then talked to Siegelaub about it. It so happened that Barry already knew this latter, whose gallery was in the neighbourhood.

The 1964 paintings and the One Million Dots possibly only have in common the organization of the repetitive motifs. The Xerox Book is a multiple, as its name suggests. The One Billion Dots is a one-off work, but it results from the repetition of 40,000 dots per page over 25,000 pages. The differentness resides in automaticity and disproportion. All that remains written by hand, if we can so put it, in the books, is the consultation they invite. For even if what interests Barry in the book is the idea of the book, this idea is intended to be tangible: "I like books. I like the idea of holding them and turning pages. It creates a physical experience, a personal time. The artist book is about being a book. It is about turning pages, going back and forth and controlling time and space32. " The idea of the book is probably not altogether the book. But is there a choice? From a book, is it possible to have an experience other than that of the idea you make of it?

Now, in order to be necessary, this idea does not need to be faithful to the book suggesting it. What is more, the book to which Barry here makes reference is a forthcoming book, both ideal and generic. Similarly, the composer Robert Schumann, in the depths of depression, still laid claim to a certain idea of happiness. "Nothing shows better how sadness is the foundation of all music of innerness than Schumann's note: "Im frohlichen Ton " [In the tone of joy]. The word joy or happiness belies its reality, and the "im ", which presupposes the existence of a "joyous tone ", known and belonging to the past, announces at one and the same time that this tone is lost and that there is the intent to bring it back to life33.

One Billion Dots has remained in the same private German collection since the 1970s. Few and far between, therefore, are those who have had a chance to consult it. The publisher Michèle Didier dreamt of publishing a new version of it ever since, in 1995, she started working on the One Million Years of On Kawara, precisely contemporary with Robert Barry's project34. She already had under her belt several monumental projects when she first met Barry and offered to make a multiple of his first billion dots. Barry turned down the offer and mentioned another book project, which would result in the 72-page Art Lovers, published by Michèle Didier in 2006. Then, when the publisher had quite given up, Barry reverted to his initial intention in 2007 and proposed the variant One Billion Colored Dots; "Same concept, different realization35 ". As an edition of thirty-five, One Billion Colored Dots appeared 40 years after the One Million Dots, 40 years after he had the idea for One Billion Dots, and 37 years exactly after the realization of this latter. Barry is used to this kind of revival: "I have done it very often in many different ways […] I like that use of time and space and time creating space. Something only an older artist can do36. " Each book in the new series of 25 has 2008 pages and it is in the year 2008 that the project has been completed. The first edition had grey binding and was printed in black inside. The new edition has white binding and is thus printed in 25 different colours, one for each volume, apart from the title and colophon pages. The meaning of a work is provided by the artist's motivation. "I always do what I say I'm going to do. [...] Ah, it's important to me to do it. You see, that's part of the making of the art37. "

Instead of looking for meaning, look for motivation!

A shelf was made to measure for the one and only very valuable One Billion Dots, an idea pursued by its owner. In the excellent catalogue published for the exhibitions at the Nuremberg Kunsthalle, and the Aarau Kunsthaus in 200338, the caption to the photo of this work mistakenly refers to the piece of furniture as part of the work. Ah, the delights of translation: in German the word for shelf is Regal — which by the way means delight in French! I have passed this on to Barry, who liked it, but not yet to Jonathan Monk, whose portrait features in the background of a page of Art Lovers, who will revel in it. Monk is actually nurturing a project to produce a series of pictures with a billion dots painted by hand in China at the rate of one dot per person39.

In French, one can choose between two etymologies for the word régal : the etymology of rejoicing or celebration, which gives rigoler [Eng. to laugh] and the etymology of royal which gives régalien [regalian or kingly.] One can find also happiness between the two.

Frédéric Paul, 2008

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Notes

1 R. B. in Patricia Norvell & Alexander Alberro, Recording Conceptual Art, interviews by P. Norvell, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2001, p. 90

2 Vol de Nuit, Gallimard, Paris, 1931, ch. XVI, republ. Folio, p. 145

3 R. B., correspondence with the author, 13 August 2008

4 In French, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Contes nocturnes, tr. M. Laval and A. Espiau de la Maëstre, Phébus, Paris, 1979, p. 61

5 Conveniently relisted under the reference An Untitled Book in bibliographies, but actually incurring an error: the book did not in fact have this title.

6 One-Dimensional Man [L'Homme unidimensionnel] appeared in French in the same year.

7 R. B., p. 26 of the catalogue

8 R. B., P. Norvell, op. cit., p. 87

9 M. B., Artforum, New York, May 1970

10 C. A., "Sensibility of the Sixties ", Art in America, January-February 1967, p. 49

11 Sperone met Siegelaub in Italy. He then went to New York to meet Barry

12 S. S., P. Norvell, op. cit., p. 33

13 Two volumes of helium were released in the Mojave desert, on two different days (one for the Californian show, the other for the exhibition March 69, in New York), and a third volume, in Los Angeles, near the pool in a friend's garden. The krypton was released in Beverly Hills. The xenon, in the Tehachapi mountains. The argon, on a beach at Santa Monica. The neon, on a hill in Los Angeles, facing the Pacific Ocean. ( And the documentation for this piece has to date never been presented. ) Because the radon could not be delivered without a permit, given its radioactivity, Barry stuck with five inert gases out of the six listed.

14 Wholeness is something else again. Because the gases used are inert, and because, by definition, "they are not part of any known chemical combination ", their dispersed molecules will always stay whole whatever their proportion in the atmosphere. Purity is a passive and residual characteristic. Wholeness is the active property of keeping this characteristic while protesting against corruption. It would be wrong to attach any moral value to a bottle of alcohol labelled 100° or 100% volume.

15 What is more, the contrast is not as candid and symmetrical as might be suggested by this bipolarization of accumulation/dispersion. For, by subtitling each piece in the inert gases series "from a measured volume to indefinite expansion ", let us note that Barry prefers the word expansion to dispersion—expansion may be inadequate, scientifically speaking, but it is no less effective when it comes to describing our imagination's infinite capacity to invent, as attested to by the invention of the infinite sequence of numbers.

16 R. B., "with as little description as possible, with as little interpretation as possible ", P. Norvell, op. cit., p. 97

17 D. H.: " A point located in the exact center of this page. ""For the single instant that it is perceived the point represented above exists as a phenomenon in time and space that is equal in value to any other position of reality that its percipient has ever considered as a measurement of his, or her existence. "

18 Related to the hardly more sensible coefficient of 10 dots per second, this would mean 3.1709 years ( i.e. 3 years, 62 days, 9 hours, 5 minutes and 2.4 seconds ), or 1 157.4074 days ( i.e. 1157 days, 9 hours, 46 minutes and 39.36 seconds ), or 27,777.7777 hours ( i.e. 27,777 hours, 46 minutes and 39.72 seconds ), or 1,666,666.666 minutes ( i.e. 1,666,666 minutes and 40.2 seconds ), and thus 100,000,000 seconds to terminate this ordeal without any other activity, and without any sleep! At a rate of one dot per second, it will take you almost 32 years of insomnia and liquidfree dieting.

If the truth be told, according to Michèle Didier, the projection of the film follows the following progression: "The image changes every half-second, i.e. there is a black screen alternation containing one or several dots and a virgin black screen every half-second.

1 second……………. screen 1 - 1 dot

25 s……………………. screen 2 - 3 dots

30 s……………………. screen 3 - 5 dots

35 s……………………. screen 4 - 9 dots

40 s……………………. screen 5 - 12 dots

45 s……………………. screen 6 - 17 dots

50 s……………………. screen 7 - 37 dots

55 s……………………. screen 8 - 68 dots (1 line)

60 s……………………. screen 9 - 204 dots

65 s……………………. screen 10 - 476 dots

70 s……………………. screen 11 - 1020 dots

75 s……………………. screen 12 - 2788 dots

When the black screen is saturated with dots, i.e. 2788..., it will flash up to the 358,753rd second, then in the opposite direction once again lose the same number of dots, in the same time, until it displays 1 dot on the screen and then it will take 1 second more to stop.

358,753 s………….. screen 11

358,759 s………….. screen 10

358,764 s………….. screen 9

358,769 s………….. screen 8

358,775 s………….. screen 7

358,780 s………….. screen 6

358,786 s………….. screen 5

358,791 s………….. screen 4

358,797 s………….. screen 3

358,802 s………….. screen 2

358,807 s………….. screen 1

358,834 s………….. final screen

358,840 s………….. stop

But it may as well be admitted, Michèle Didier and I have never managed to agree over the exact length of the film! To those unfortunate people who were not aware of this, let us mention in this respect, to get on a beam with and on the right side of Robert Barry, that according to the first resolution of the 13e Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures, 1967/68 : "The second is the duration of 9 192 631 770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium 133 atom ".And let us add, for greater accuracy, that: "This definition refers to a caesium atom at rest at a temperature of 0 K. "

19 Sartre, Qu'est-ce que la littérature?, "1. Qu'est-ce qu'écrire ? ", Gallimard, Paris, 1948, republ. Folio, 1985, p. 14

20 R. B., correspondence with the author, 18 July 2008

21 Ibid

22 Sartre, op. cit., p. 30

23 M. B., Anne-Françoise Penders, "Rencontre avec Mel Bochner / New York, mars 2000 ", Pratiques, n° 9, École des beaux-arts/Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Autumn 2000

24 M. B., "Speculations 1967-1970 ", Art in the Mind, Allen Art Museum / Oberlin College, Oberlin ( Ohio ), 1970, p. 33

25 R. B., P. Norvell, op. cit., p. 91

26 S. S., ibid, p. 33

27 Let us think once again of Marcuse and note that Siegelaub, who does not see himself as a theoretician and even less as a writer, published Marxism and the Mass Media 4-5, in 1976, and Communication and Class Struggle: Capitalism, Imperialism, en 1979.

28 R. B., correspondence with the author, 19 July 2008

29 R. B., ibid., 20 July 2008

30 Sartre, op. cit., pp. 27, 28

31 R. B., P. Norvell, op. cit., p. 94

32 R. B., Interview in Brussels on the 22 nd of March 2006 by Vera Kotaji for Michèle Didierw. ww.micheledidier.com

33 Theodor W. Adorno, Quasi una fantasia, Gallimard, Paris, 1982, p. 13

34 On Kawara's project was finalized in 1999 by Editions Micheline Szwajcer & Michèle Didier.

35 R. B., correspondence with the author, 20 July 2008

36 R. B., ibid

37 R. B., P. Norvell, p. 90

38 Karl Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld, 1986, p. 59

39 J. M., correspondence with the author, 21 July 2008: "...wanted to make a series of paintings with one billion dots / hand painted in China / one dot per person "

12.2 x 10.63 in ( 31,7 x 27 cm )

11.02 x 8.27 in ( 28 x 21,5 x 0,6 cm )

6.69 x 4.72 x 1.57 in ( 17,4 x 12,4 x 4,9 cm )

10.63 x 10.63 in ( 27,6 x 27,6 cm )